|

The earliest exhumations from the City Cemetery began when Rosehill, Chicago's first rural cemetery, opened its doors in August, 1859. The city officials enacted an ordinance prohibiting further sales of burial lots in the City Cemetery, effective May 1, 1859. It is not clear how arrangements were made during the three interim months, for burials of those who did not already own lots in the municipal cemetery. Individual graves were available in the City Cemetery potter's field. Burials continued in previously-owned lots and the potter's field until March, 1866. In an arrangement with the city officials, Rosehill Cemetery was to have allotted a section within their grounds for inexpensive single lots. This allotment was a consideration for individuals without families, and for those without the means for buying more expensive, larger burial lots. Newspaper articles indicate that this arrangement did not last very long.

It is not clear to me how many interments were made at Rosehill Cemetery during their first year. From my experience conducting research for this project, it appears that Rosehill may no longer have those early records. See more about Rosehill Cemetery, here.

In 1860, Graceland Cemetery, and the Catholic Calvary Cemetery, opened their grounds for burials. During Graceland's inaugural year, there were twenty-one reinterments from the City Cemetery. Daniel Page Bryan, the son of Thomas B. Bryan, the founder of Graceland Cemetery, was the burial, a reinterment from the City Cemetery. See the Graceland Cemetery interment book records, detailing the reinterments from the City Cemetery, here. Although Calvary Cemetery officials claim to have the records of the reinterments from the old Catholic Cemetery, I was unable to access that information.

According to Dr. John H. Rauch, the City Cemetery and potter's field burials numbered 15,212 from 1860 through the beginning of 1866. During this same period, Graceland Cemetery reinterred 565 sets of remains from the City Cemetery. In 1866 and 1867, during the Milliman Tract removals, Graceland received 550 sets of remains. It seems fair to say that Rosehill Cemetery received similar total numbers from the City Cemetery as Graceland Cemetery did, even though Graceland was recorded to have received twice as many removals from the Milliman Tract than Rosehill. Oak Woods Cemetery, on Chicago's South Side, received similar numbers from the City Cemetery. After the claimed burial lots were removed to the other cemeteries, the remaining marked graves were removed to a 27,000 square foot tract of land within Oak Woods. See the final resting place for those unclaimed City Cemetery bodies, here.

After the Milliman Tract was returned to the Milliman heirs, City Cemetery lot owners removed their family lots at their own expense to the newer rural cemeteries. There was no major movement to actively vacate the cemetery until the 1871 Chicago Fire. From 1868 through 1871, Graceland Cemetery recorded the reinterment of 614 sets of remains from the City Cemetery.

From November 1871, the month after the Chicago Fire, until the late 1880s, disinterments continued from within the City Cemetery. In 1869, the Lincoln Park Commissioners took responsibility for vacating the cemetery grounds and incorporating that land into Lincoln Park. Listen to a conversation with Julia Bachrach, the Chicago Park District Historian about early Lincoln Park, here.

More information about disinterments and burials within the City and Catholic Cemeteries can be seen in The Numbers section.

More information about the factors relating to the vacation of the City Cemetery and its transition into Lincoln Park can be seen in the Contributing Factors in Moving the Cemetery section. |

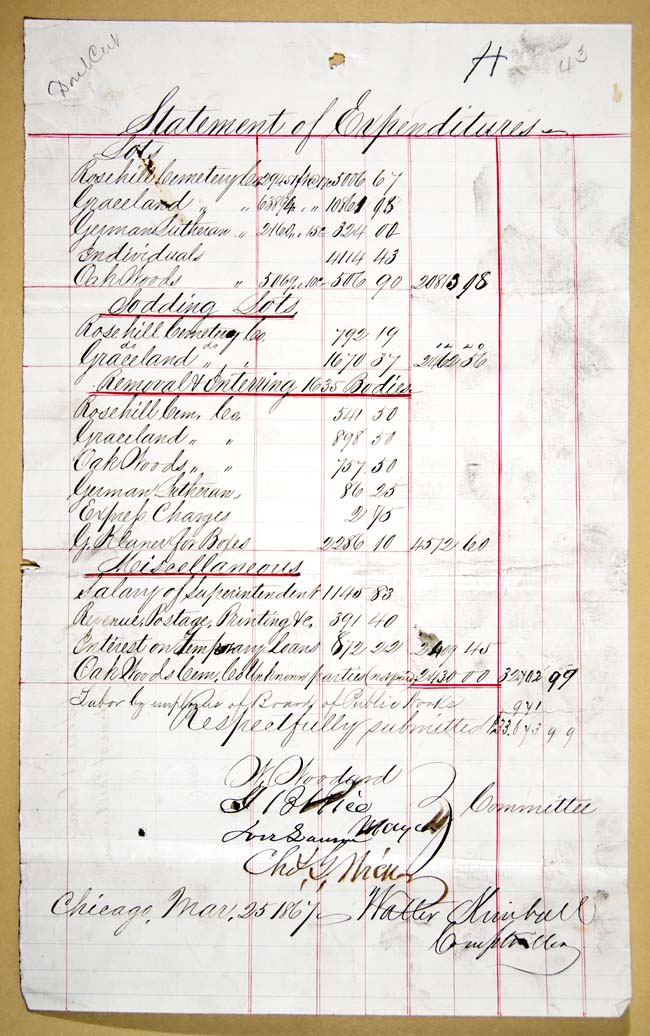

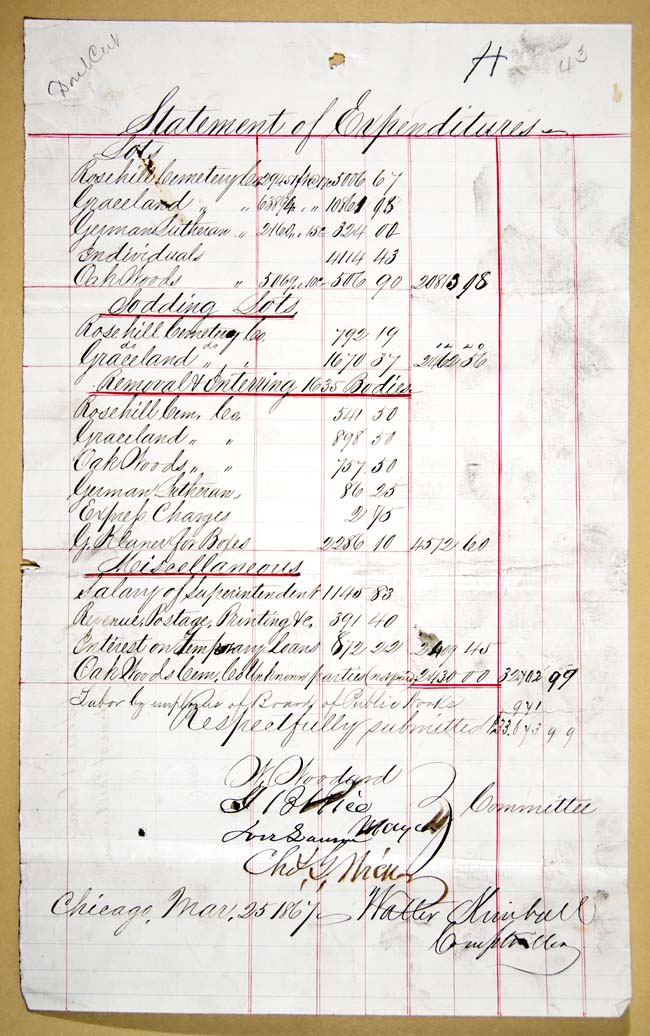

March 25, 1867, Costs for disinterring bodies from the Milliman Tract

Courtesy of the Illinois Regional Archives Depository.

|

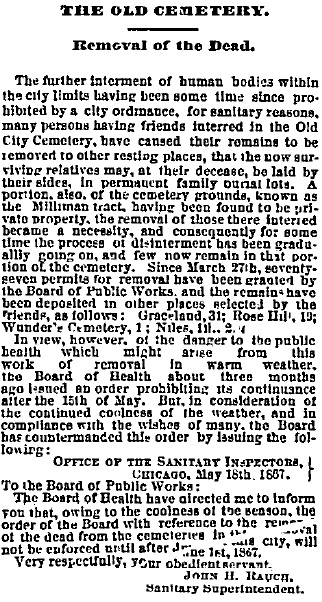

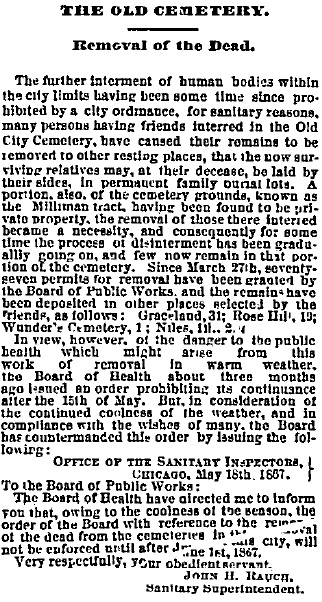

Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1867

|

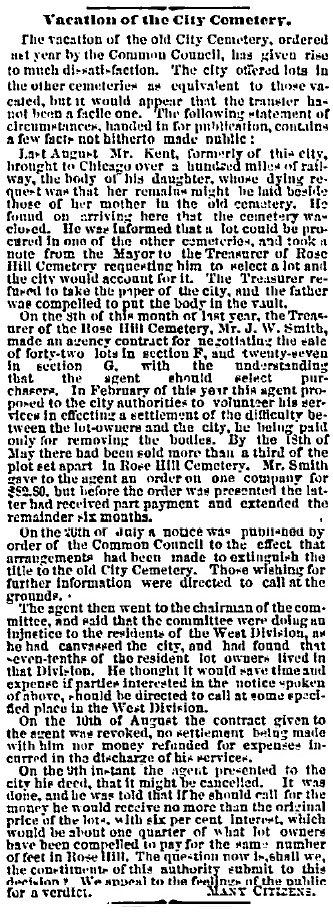

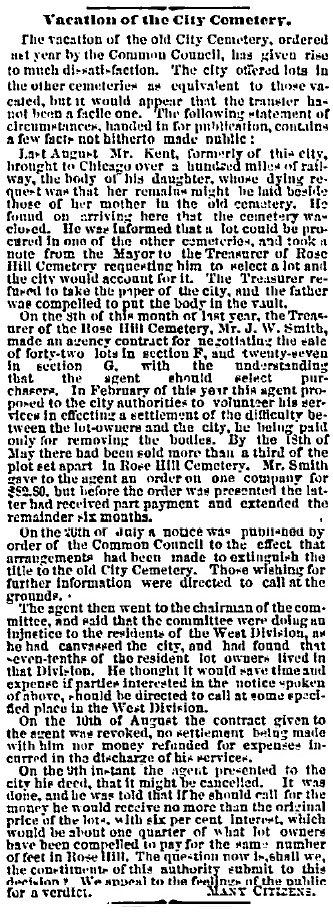

Chicago Tribune, September 19, 1867

|

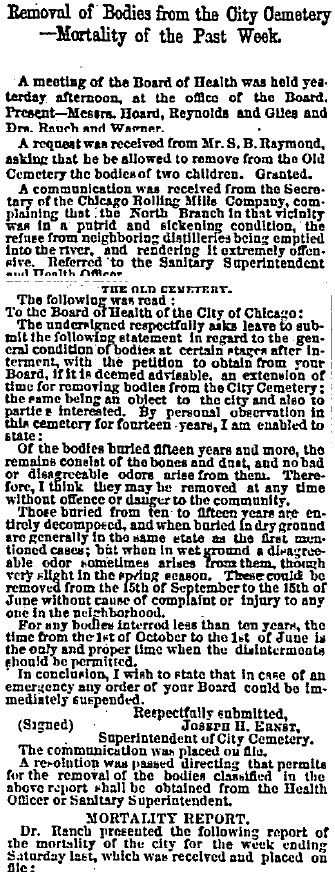

Chicago Tribune, September 24, 1867

|

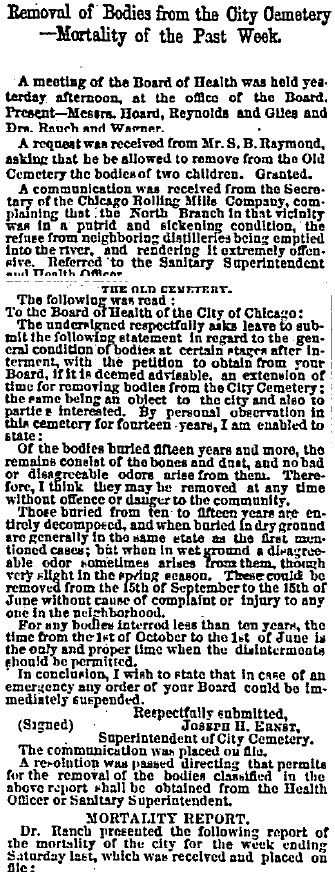

Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1870

The Cemetery Lots.

We print the report of the Superintendent of the City Cemetery on the subject of the removal of the bodies from the lots in that place. No removals have been made from one-half the lots sold by the city, and of the 25,000 bodies in the Potter’s Field, not one has been removed. The difficulties in the cases of the lot-holders are irremediable by any power possessed by the city, nor do we understand how the city can act in the case of the unknown dead, buried in the Potter’s Field. The cemetery has become anything but a proper place for such a purpose. It is rapidly falling into decay. Something ought to be done in the matter to remove the eye-sore which the cemetery grounds now are.

It is understood that the Commissioners of Lincoln Park have the power to condemn this land for park purposes, and, if they have, perhaps that is the clearest and shortest process to apply to the difficulty. If lot-holders will not exchange lots, and will not remove the bodies, then the Commissioners may take the land, making due compensation therefore, and make such disposition of the unclaimed bodies as decency and propriety may suggest. It is stated that some lot-holders cannot be found, and that others are minors, unable to consent to an exchange of lots. However these difficulties may prevent a voluntary surrender of the cemetery lots they cannot prevent the condemnation of the land by the Commissioners for public purposes, nor prevent them taking such proper action with regard to the removal of the bodies as circumstances may require. The Commissioners, however, while they have the power to condemn land, are at present without the power to pay for it – that is, under the Legislation of 1869, no provision was made for taxation. Additional legislation will be required to remedy this defect, and then, possibly, we may have a direct means of disposing of the cemetery troubles. |

Chicago Tribune, September 18, 1872

THE STRIDE OF PROGRESS

Removal of the Bodies from the Old City Cemetery.

The Remains of Over 10,000 Dead Persons Still to Be Taken Away.

The remnants of the old city of Chicago are rapidly becoming things of the past. One by one the old landmarks fall under the sacrilegious hand of progress, and are obliterated from the mind and vision. The old Chicago Cemetery, a portion of which is so well known as the “Potter’s Field,” has been consigned to oblivion. This place of interment is one of the few remaining links connecting the early history of the city with the Chicago of to-day. The authorities have decided that the ground comprising the old cemetery shall be embraced within the now somewhat circumscribed boundaries of Lincoln Park. It is not proposed to secure this property in fee to the city, unless some equivalent is rendered to those who have held it for so many years. The city, therefore, very generously agrees to allow the former owner a lot, equal in size to the one vacated, in any cemetery the owner may specify; and, in addition, proposes to liquidate all expenses incurred in exhuming and transporting the remains to their new resting places. The unclaimed, or unknown coffins, will be deposited in the county burying ground at Jefferson.

The work of disinterring commenced on Monday afternoon. Ten men are assigned to perform this duty, and this force is enabled, in the course of a day’s work, to exhume about twenty bodies. These are immediately boxed, and a proper disposal made of them. The greatest care is exercised in this work. The men labor zealously to secure and properly arrange every bone, as they are disinterred, for future burial. In the case of the unknown dead, the numbers are placed with the remains, and will be affixed to the graves in the County Cemetery. The better class of people, however, take personal charge of the remains of their own relatives. There are in this cemetery about 10,000 dead. Some time will be consumed before the work can be consummated.

The disinterred bodies present several as well as curious phases, and might be made the subject of interesting scientific research. Some are exhumed in a perfect state of adipoceration. In some instances the bodies appear as perfect as though they were interred but yesterday; but handle them never so tenderly, and they crumble away like earth. In some cases, an indistinguishable mass of rotten bones and wood are all that remains of the “temple of the soul.”

A skeleton, arranged for anatomical lectures, could not be constructed, apparently, better than some of the remains disinterred, yesterday. Every bone occupied in its natural position, the vertebrae, the muscles, the skull, all remain in an apparently perfect state. But that long period of interment has influenced all, so that, like the apples of the Dead Sea, they are curious to look upon, but crumble to ashes at the slightest touch.

The disappearance of this old burial place will be mourned by many. There are memories clustered around this old spot too sacred to be disturbed by the hand of the invader; and those whose beloved dead rest here will, more than all, wish that it might remain. But idealism, in the present day, must make way for materialism.

The bones of about 2,000 Confederates who died at Camp Douglas, and were buried in the Potter’s field were removed to Jefferson some months since.

October 13, 1872 Chicago Tribune

Potter’s Field.

Before another Sunday all the dead will have been removed from the Potter’s Field in that part of Lincoln Park lying between Dearborn road and the lake, and transferred to the county property, in the town of Jefferson, eight miles northwest of the Court House. |