|

David Kennison seems to have arrived in Chicago in 1848.

His legacy should show that he was a masterful public relations man, even if sometimes his own stories were misconstrued.

_______________________________________

The very first published item I encountered that mentioned him is inaccurate on more than one count.

New York Evangelist, March 2, 1848

______________________________________

______________________________________

The following month, another Chicago newspaper issued its report:

Chicago Weekly Democrat, April 18, 1848

David Kennison, one of the patriots who threw tea overboard in Boston Harbor, is now lion of this city. The old gentleman is 111 years of age, and will be, if he lives until the 17th of November, 112. He served not only through the campaign of the glorious Revolution, but in the war of 1812. He is in receipt of a pension from the General Government.

______________________________________

Then, he appeared again in an excerpt from an article under the heading, "History and Biography. Original, Life of Washington and History of the American Revolution, No. 9, 1773-1774. The Boston Tea Party."

The Youth's Companion, June 29, 1848

______________________________________

Chicago Daily Journal, November 18, 1848

The last survivor of the Boston Tea party.

We have been applied to for the purpose of calling the attention of the public to the fact that Mr. David Kennison, who is represented to be 112 years old, and one of the party that threw the tea overboard in Boston Harbor, in the Revolution, is now the lessee of the Chicago Museum, and would be happy to receive visits from his friends.

It is a fact that Mr. Kennison is as old as he represents himself to be, and so needy withal, a soldier of the Revolution, we think patriotism is at a low ebb in Chicago if it will permit itself to be thus represented and hawked about the streets by the cents worth, as a show.

A subscription for the old man, if he is worthy, to render him comfortable for the remnant of his days, would be far more creditable to the community.

|

Chicago Daily Democrat, November 6, 1848:

"I have taken the Museum in this city, which I was obliged to do in order to get a comfortable living, as my Pension is so small it scarcely affords the comforts of life. If I live until the 17th of November, 1848, I shall be 112 years old, and I intend making a Donation Party on that day at the Museum. I have fought in several battles for my country, and have suffered more than any man will have to suffer, I hope I would not go through the wars , and suffer what I have, for ten worlds like this. Now all I can ask of this generous public is to call at the Museum on the 17th day of November, which is my birthday, and donate to me all they may think I deserve. I shall be happy to have all the traveling community call and see me at all times."

|

In 1848, Kennison writes to the Chicago Democrat newspaper, detailing his amazing biographical military history.

___________________________

Sir: As several persons have been to see me to know how I was going to vote, I wish to get from you the use of the Democrat to tell the people what conclusion I have come to in the present condition of my country, as I probably shall never have another opportunity of voting. I have thought much of the subject, knowing my responsibility to God and my country. If I live till the 17th day of November next, I shall be one hundred and twelve years old.

I was born at Kingston, New Hampshire, and my father moved to Lebanon, Maine, when I was an infant. I was a citizen of that place when, at the age of about thirty-three, I assisted in throwing the tea overboard in Boston harbor. I was at the battle of Bunker Hill and stood near General Warren when he fell. I also helped roll the barrels, filled with sand and stone, down the hill as the British came up.

I was at the battles of White Plains, West Point, and Long Island. I helped stretch the chain across the Hudson River to stop the British from coming up. I was also in battles at Fort Montgomery, Staten Island, Delaware, Hudson, and Philadelphia. I witnessed the surrender of Lord Cornwallis, and was near West Point when Arnold betrayed his country and Andre was hung. I have been under Washington (for whom I frequently carried the mails and dispatches), Prescott, Putnam, Montgomery and Lafayette. I now draw a pension of eight dollars a month for services in the Revolutionary war.

When the last war broke out, I was living at Portland, Maine, when I enlisted and marched to Sackett’s Harbor, and was in battle at that place, and also at other places, and now bear the marks of a wound received in my hand in that war. I voted for Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson, Van Buren, and Polk, and have thought that I ought to vote for Mr. Van Buren at this time. I am a strong “free soil” man and spoke at the free soil meeting in this city on the Fourth of July last. I have always been a Democrat and think it is too late to change now, even if I had a disposition, which I have not. I have made up my mind that Mr. Van Buren stands no chance of an election, and that voting for him will endanger the success of the other Democrats in this field, and so give us a Whig for president; hence I shall cast my vote for General Lewis Cass for president and General William O. Butler for vice-president, and advise all other Democrats to do the same.

David Kennison. |

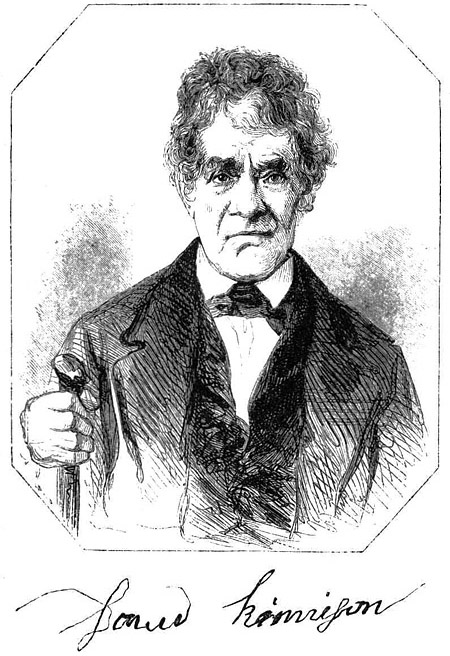

In 1850, David Kennison was said to have been interviewed to be included in Benson J. Lossing's, Pictorial Fieldbook of the Revolution. The illustration, at the left, is from that book. The entry, below, and the signature under the illustration, show the Kennison name as Kinnison, the way he spelled it himself.

It was from this published account that the Kennison legend grew.

_____________________________________________________

This is DAVID KINNISON, of Chicago, Illinois, whose portrait and sign manual are here given. The engraving is from a Daguerreotype from life, taken in August, 1848, when the veteran was one hundred and eleven years and nine months old. He was alive a few weeks since (January, 1850), in his one hundred and fourteenth year. Through the kindness of a friend at Chicago, I procured the Daguerreotype, and the following sketch of his life from his own lips. The signature was written by the patriot upon the manuscript.

DAVID KINNISON was born the 17th of November, 1736, in Old Kingston, near Portsmouth, province of Maine. Soon afterward his parents removed to Brentwood, and thence in a few years to Lebanon (Maine), at which place he followed the business of farming until the commencement of the Revolutionary war. He is descended from a long-lived race. His great-grandfather, who came from England at an early day, and settled in Maine, lived to a very advanced age; his grandfather attained the age of one hundred and twelve years and ten days; his father died at the age of one hundred and three years and nine months; his mother died while he was young.

He has had four wives, neither of whom is now living; he had four children by his first wife and eighteen by his second; none by the last two. He was taught to read after he was sixty years of age, by his granddaughter, and learned to sign his name while a soldier of the Revolution, which is all the writing he has ever accomplished.

He was one of seventeen inhabitants of Lebanon who, some time previous to the "Tea Party," formed a club which held secret meetings to deliberate upon the grievances offered by the mother country. These meetings were held at the tavern of one "Colonel Gooding," in a private room hired for the occasion. The landlord, though a true American, was not enlightened as to the object of their meeting. Similar clubs were formed in Philadelphia, Boston, and the towns around. With these the Lebanon Club kept up a correspondence. They (the Lebanon Club) determined, whether assisted or not, to destroy the tea at all hazards. They repaired to Boston, where they were joined by others; and twenty-four, disguised as Indians, hastened on board, twelve armed with muskets and bayonets, the rest with tomahawks and clubs, having first agreed, whatever might be |

the result, to stand by each other to the last, and that the first man who faltered should be knocked on the head and thrown over with the tea. They expected to have a fight, and did not doubt that an effort would be made for their arrest. "But" (in the language of the old man) "we cared no more for our lives than three straws, and determined to throw the tea overboard. We were all captains, and every one commanded himself." They pledged themselves in no event, while it should be dangerous to do so, to reveal the names of the party – a pledge which was faithfully observed until the war of the Revolution was brought to a successful issue.

Mr. Kinnison was in active service during the whole war, only returning home once from the time of the destruction of the tea until peace had been declared. He participated in the affair at Lexington, and, with his father and two brothers, was at the battle of Bunker Hill, all four escaping unhurt. He was within a few feet of Warren when that officer fell. He was also engaged in the siege of Boston; the battles of Long Island, White Plains, and Fort Montgomery; skirmishes on Staten Island, the battles of Stillwater, Red Bank, and Germantown; and, lastly, in a skirmish at Saratoga Springs, in which his company (scouts) were surrounded and captured by about three hundred Mohawk Indians. He remained a prisoner with them one year and seven months, about the end of which time peace was declared. After the war he settled at Danville, Vermont, and engaged in his old occupation of farming. He resided there eight years, and then removed to Wells, in the state of Maine, where he remained until the commencement of the last war with Great Britain. He was in service during the whole of that war, and was in the battles of Sackett’s Harbor and Williamsburg. In the latter conflict he was badly wounded in the hand by a grape-shot, the only injury which he received in all his engagements.

Since the war he has lived at Lyme and at Sackett’s Harbor, New York. At Lyme, while engaged in felling a tree, he was struck down by a limb, which fractured his skull and broke his collar-bone and two of his ribs. While attending a "training" at Sackett’s Harbor, one of the cannon, having been loaded (as he says) "with rotten wood," was discharged. The contents struck the end of a rail close by him with such force as to carry it around, breaking and badly shattering both his legs midway between his ankles and knees. He was confined a long time by this wound, and, when able again to walk, both legs had contracted permanent "fever sores." His right hip has been drawn out of joint by rheumatism. A large sear upon his forehead bears conclusive testimony of its having come in contact with the heels of a horse. In his own language, he "has been completely bunged up and stove in." |

When last he heard of his children there were but seven of the twenty-two living. These were scattered abroad, from Canada to the Rocky Mountains. He has entirely lost all traces of them, and knows not that any are still living.

Nearly five years ago he went to Chicago with the family of William Mack, with whom he is now living. He is reduced to extreme poverty, and depends solely upon his pension of ninety-six dollars per annum for subsistence, most of which he pays for his board. Occasionally he is assisted by private donations. Up to 1848 he has always made something by labor. "The last season," says my informant, "he told me he gathered one hundred bushels of corn, dug potatoes, made hay, and harvested oats. But now he finds himself too infirm to labor, though he thinks he could walk twenty miles in a day by ‘starting early.’ "

He has evidently been a very muscular man. Although not large, his frame is one of great power. He boasts of "the strength of former years." Nine years ago, he says, he lifted a barrel of rum into a wagon with ease. His height is about five feet ten inches, with an expansive chest and broad shoulders. He walks somewhat bent, but with as much vigor as many almost half a century younger. His eye is usually somewhat dim, but, when excited by the recollection of his past eventful life, it twinkles and rolls in its socket with remarkable activity. His memory of recent events is not retentive, while the stirring scenes through which he passed in his youth appear to be mapped out upon his mind in unfading colors. He is fond of martial music. The drum and fife of the recruiting service, he says, "daily put new life into him." "In fact," he says, "it’s the sweetest music in the world. There’s some sense in the drum, and fife, and bugle, but these pianos and other such trash I can’t stand at all."

Many years ago he was troubled with partial deafness; his sight also failed him somewhat, and he was compelled to use glasses. Of late years both hearing and sight have returned to him as perfectly as he ever possessed them. He is playful and cheerful in his disposition. "I have seen him," says my informant, "for hours upon the side-walk with the little children, entering with uncommon zest into their childish pastimes. He relishes a joke, and often indulges in ‘cracking one himself.’ "

At a public meeting, in the summer of 1848, of those opposed to the extension of slavery, Mr. Kinnison took the stand and addressed the audience with marked effect. He declared that he fought for the "freedom of all," that freedom ought to be given to the "black boys," and closed by exhorting his audience to do all in their power to ABOLISH SLAVERY. |

The Chicago Evening Post, as part of a June 14, 1894 article detailing the placing of a flag on his burial site, published this statement which it said was written by David Kennison:

|

I, David Kennison, was born on the 17th of November, 1736, in Old Kingston, near Portsmouth, Province of Maine. Soon afterward my parents removed to Brentwood, and thence in a few years to Lebanon, Me., at which place I followed the business of farming until the commencement of the revolutionary war. I am descended from a long-lived race. My great grandfather, who came from England at an early day and settled, lived to the age of 112 years and 10 days. My father died at the age of 103 years and 9 months. I had four wives, none of whom are now living. I had four children by my first wife and eighteen by my second; none by the last two. I was taught to read after I was 60 years of age by my granddaughter and learned to sign my name when a soldier of the revolution, which is all the writing I have ever accomplished.

I was one of the seventeen inhabitants of Lebanon who, some time previous to the "Tea Party," formed a club which held secret meetings to deliberate upon the grievances inflicted by the mother country. These meetings were held at the tavern of one Colonel Gooding, in a private room for the occasions. The landlord, though a true American, was not enlightened as to the object of these meetings. Similar clubs were formed in Boston, Philadelphia, and all the towns around. With these the Lebanon clubs kept up a correspondence. the Lebanon Club determined - whether assisted or not - to destroy the tea at all hazards. They repaired to Boston, where they were joined by others, and twenty-four, disguised as Indians, hastened on board, twelve armed with muskets and bayonets, the rest with tomahawks and clubs, having first agreed, whatever might be the result to stand by each other to the last and that the first man who faltered should be knocked on the head and thrown over with the tea. We expected to have a fight, and did not doubt that an attempt would be made to arrest us. But we cared no more for our lives than three straws, and determined to throw the tea overboard. We were all captains and each one commanded himself. We pledged ourselves that in no event, while it would be dangerous to do so, to reveal the name of any one of the party - a pledge which was faithfully kept until the war of the revolution was brought to a successful issue.

I was in active service during the entire war, only returning home once from the time of the destruction of the tea until peace was declared. I was within a few feet of Warren when that officer fell. I was engaged in the siege of Boston and was in the battles of Long Island, White Plains and Fort Washington: was in skirmishes on Staten Island and in the battles of Brandywine, Red Bank and Germantown, in which my company of scouts was surrounded and captured by about three hundred Mohawk Indians. I remained a prisoner with them one year and seven months, about the end of which time peace was declared. After the war I settled at Danville, Vt., and engaged in farming. I resided there eight years and then removed to Wells, Me., where I remained until near the commencement of the war of 1812 with Great Britain. I was in the service during the whole of that war at various places. A wound in the hand by a grape shot was the only injury I ever received in all the engagements I participated in.

Since the war I have lived at Lyme and at Sackett's Harbor, New York. At Lyme, while engaged in felling a tree. I was struck down by a limb, which fractured my skull and broke my collar bone and two ribs. While attending a "training" at Sackett's Harbor one of the cannon, loaded with rotten wood, was discharged. The contents struck the end of a rail close by me with such force as to carry it around, breaking and badly shattering both my legs between the ankles and knees. My right hip was drawn out of joint by rheumatism. The scar upon my forehead is from a hurt given by the kick of a horse. I have been bunged up and stove in many times, but never badly in war.

When last I heard of my children there were but seven of the twenty-two living. These were scattered from Canada to California. For some years I have lost all trace of them, and knew not whether any are still living. Nearly six years ago I came to Chicago and entered the family of William Mack, with whom I am now living.

David Kennison

Chicago, Jan 14, 1850.

[The Chicago press noted Kennison's arrival in the city in 1848. Other accounts have had him arriving with the family of William C. Mack. Kennison's statement has him arriving in Chicago in 1845, whereupon he joined the Mack family.] |