| |

1852 - 1896

1897 - 1901

Fernando Jones

A monument to honor David Kennison was not erected during the tenure of the city officials who had agreed to the suggestion at the time of his death.

This letter to the Editor of the Chicago Press and Tribune is the first item I found related to the city's neglect in following up on their promise to memorialize Kennison. Written on the anniversary of George Washington's birthday, and seven years after Kennison's passing, this writer (spelling Kennison as Kinnison) notes all the originally intended plans that were mentioned at the time of the funeral.

More than two decades passed before the name David Kennison appeared again in the Chicago Tribune.

|

Twenty-one years later, the Kennison legacy is revived.

|

Fourteen years later, three men placed a flag in Lincoln Park, near the spot where they believed David Kennison was buried. They claimed they were at the funeral forty-two years earlier, and were the only people who knew the correct location of the grave.

This is the first mention of Fernando Jones, who will figure into the David Kennison story again later.

(See the Fernando Jones tab, above, and The Artifacts section.)

|

|

Two years later, David Kennison is recalled again.

In the Chicago Daily Tribune article, below, Fernando Jones, et.al., argue with Joseph Ernst

about the location of the Kennison gravesite.

Joseph Ernst was the City Sexton during the disinterment years of the 1870s.

(See some of his disinterment records here.)

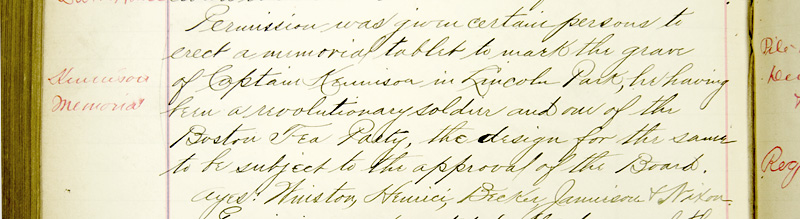

This is the first Kennison citation in the Lincoln Park Commissioners' proceedings. |

Chicago Press and Tribune, February 22, 1859

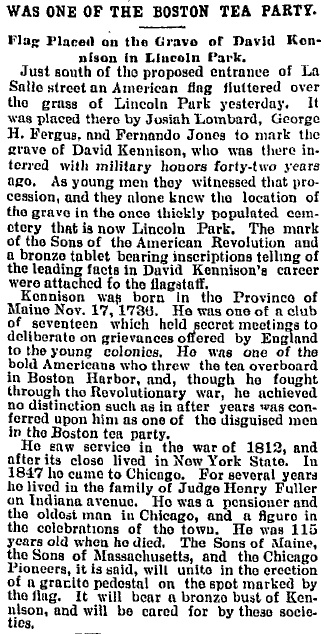

THE LAST SURVIVOR OF THE BOSTON TEA PARTY.

Messrs. Edtors:- I notice with pleasure the arrangements being made to celebrate the 22d. This is right, and I hope it may have the effect intended on this community, which will be a happy reward for the attention and efforts of those who have made the movement. On such an occasion, when the memory is in full play, and the patriotism ample, let us call up a few of those sould stirring events, and the memory of those master spirits, so closely blended with the memory of Washington. I feel it to be my duty to call the attention of citizens to a duty, long deferred, and I fear nearly forgotten, the payment of a suitable tribute, and particularly, a proper monument to the memory of David Kinnison, the last of that noble band, the Boston Tea Party. We felt pleased, and may say honored, at having this interesting and good old man spend the last few years of his life in our midst. It would be very interesting to any one, not familiar with his history, and who were not witnesses of the great demonstration, and the unversal interest manifested on the day of his burial, to refer to our city papers of that date. Our city authorities at that time set apart, and bestowed an ample lot in the cemetery, on which he rests. Nothing was done in the burial save to replace the earth, it being well understood that his monument was to be erected very soon. Years have passed. The busy world goes whirling by, and had not faithful old "Jo," of the cemetery been spared, I doubt if anyone could now point out the lot - and if there, they could not, without aid, find any trace or sign of the grave. There are a few persons who know why it is proper for me to manifest a particular interest in this matter. I well remember the commendable interest which you took in gathering from him and preserving the interesting incidents of his life, as well as your general kindness towards him. Hence I am induced, through your valuable paper, to call attention to the subject.

Truly yours, Edward Simons. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, April 4, 1880

Who Can Tell?

To the Editor of the Chicago Tribune.

Chicago, March 30. - In the spring of 1852 there died in Chicago a Revolutionary soldier by the name of David Kennison, who was born in old Kingston, Province of New Hampshire, Nov. 17, 1736, and was 115 years 3 months and 7 days old at the time of his death. He was one of seventeen who went from Lebanon to Boston, where they were joined by others, making their number twenty-four, who, disguised as Indians, and twelve of them armed with muskets and bayonets, the rest with tommahawks and clubs, mutually agreed that if any one of them faltered he should be knocked in the head and thrown overboard. Thus equipped they boarded the english ship in the harbor and destroyed her cargo of tea by throwing it overboard, and escaped. He participated in the battles of Lexington and Bunker Hill, standing within a few feet of Gen. Warren when that officer fell. He served his country faithfully during the stirring events of the Revolution, and was in the army during the whole war, being in the battles of Long Island, White Plains, Fort Montgomery, the skirmish of Staten Island, the battles of Stillwater, Red Bank, and Germantown. Lastly, in the skirmish at Saratoga Springs, he with his company (scouts) was captured by about 300 Indians, by whom he was detained a prisoner about a year and seven months. After his release he settled in Danville, Vt. and engaged in farming. He was cared for in his last days by a family by the name of Mack, with whom he came to Chicago in 1845. They resided somewhere on the West Side. His funeral was attended by the military of Chicago. It is thought that the Chicago Battery, Capt. Smith, and the Montgomery Guards, Capt. Gleason, formed the escort, firing the usual salute at the grave.

Now, here is one of the members of the famous "Boston tea party" who is or was interred in the old cemetery, and the question is, Can anyone who is now living identify the spot where he is buried? or are there any records or maps of the old cemetery still in existence, so that the grave can be found? The writer has in an old scrapbook a biographical notice of his life and death, taken from one of the Chicago papers published at the time, which is at the service of any member of our Historical Society if it is wished, and who will render all the assistance in his power to identify the spot where he is buried. Here is a hero who, though humble in life, did as much, according to his abilities, for his country as anyone who participated in the Revolution, and it is certainly wrong for a people as patriotic as the citizens of Chicago certainly to neglect to mark the spot where his is buried in some suitable manner.

In looking over the ground recently the changes that have been wrought in the locality makes it difficult to precisely fix the spot where he is buried, but it is believed that the west curb line of La Salle street, which would cross Clark street diagonally and intersect the old cemetery fence line, is within a few yards of the spot.

XX.

________________________________

XX's letter to the editor did not elicit any responses to his question of the location of Kennison's grave, but it did prompt a direct reply from William C. Mack. Although in his only voice to this newspaper, he did not shed any light on his knowledge of the location of the grave, he did add another war story to the Kennison legacy.

___________________________________

Chicago Daily Tribune, April 7

DAVID KENNISON.

To the Editor of The Chicago Tribune.

Chicago, April 5. - I noticed in Sunday's Tribune a communication relating to David Kennison, one of the Boston Tea-Party. The letter was headed, "Who Can Tell?" and was signed "XX." I would very much like to communicate with "XX," if he will be so kind as to send me his address, and direct to the northeast corner of Forty-seventh street, and Drexel boulevard, as we all should reverence the memory of the hero of two wars. He was a Captain and led a company of militia in Sackett's Harbor, N.Y., in the War of 1812-'14. He lived with me the last ten years of his life, and died at my tne residence, corner of Madison and Jefferson streets, West Side. I have his picture. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 15, 1894

|

The Chicago Evening Post, June 14, 1894 (excerpts)

Over a plot on the greensward of Lincoln Park, just a little south of the proposed entrance to LaSalle avenue, flutters an American flag today to mark the resting place of David Kennison, the last to die of the participators in the historical Boston “tea party.” To this spot, where the bodies of heroes lay thickest when the Chicago cemetery was situated there, Fernando Jones, George H. Fergus, and Josiah Lombard, three aged pioneers, went today to pay respect to the memory of one of the nation’s patriots. They alone know where David Kennison lies buried, and this being the anniversary of the day on which the American flag was designed makes an appropriate occasion. …

At 11 o’clock this morning these three boys of former days, now grown to ripe old age, located the grave and decorated it with the official mark of the Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Josiah Lombard and Fernando Jones are respectively president and historian of the Society of the Sons of the American Revolution and George H. Fergus is secretary of the Society of Pioneers of Chicago. They have kept careful track of the Kennison grave since the tract of land was changed from a burial ground to a park, and today they drove to the spot and fixed on the bronze marker a flag and the following tablet:

Hic Jacet.

David Kennison – the last of the Boston tea party.

Born in the Province of Maine, Nov. 17, 1736.

Died in Chicago, Illinois, Feb. 24, 1852. Aged 115 years, 3 months and 17 days.

Buried with military honors in the old Chicago Cemetery, now Lincoln Park.

May His Soul Rest in Peace.

The Sons of Maine and the Sons of Massachusetts will join with the Chicago pioneers in erecting a granite pedestal on the spot. This will bear a bronze bust of the patriot Kennison. The grave will always be cared for by the members of the patriotic societies. |

By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.

Lincoln Park Commissioners Proceedings, June 3, 1896

By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.

Lincoln Park Commissioners Proceedings, June 3, 1896

Permission was given certain persons to erect a memorial tablet to mark the grave of Captain Kennison in Lincoln Park, he having been a revolutionary soldier and one of the Boston Tea Party, the design for the same to be subject to the approval of the Board.

Ayes: Winston, Henrici, Becker, Jamison & Nixon.

_______________________________________

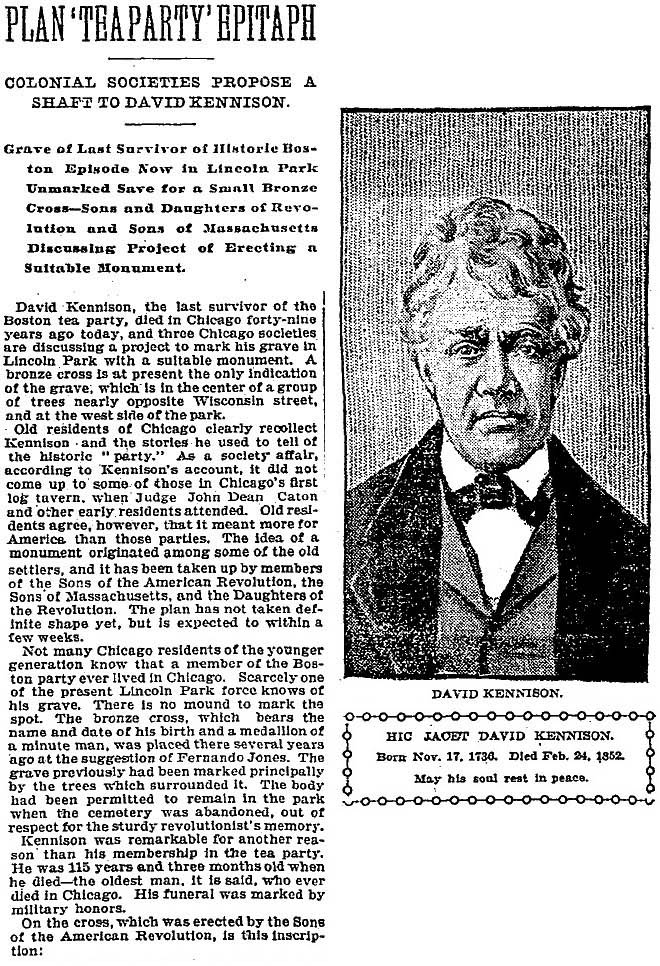

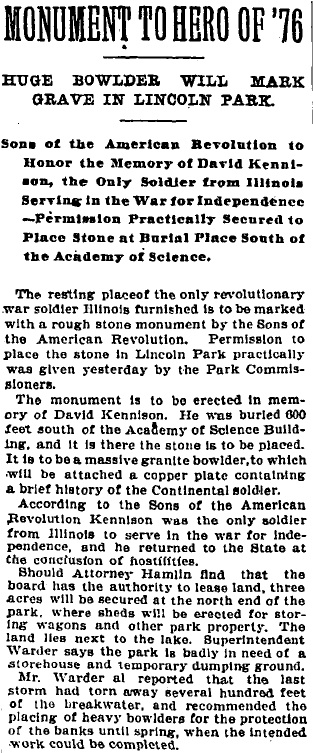

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 10, 1896

FIX THE TOMB OF A HERO.

Grave of David Kennison Nearly Located in Lincoln Park

Committee of the Sons of the American Revolution Seeks the Last Resting Place of a Colonial Patriot – Memorial Statue Will Mark a Historic Spot – Archives of the City Are to Be Searched to Confirm Funeral Memoirs.

The grave of David Kennison, patriot and revolutionary hero, who died in Chicago at the age of 115, was located within a few feet in Lincoln Park yesterday afternoon by a committee composed of members of the Sons of the American Revolution.David Kennison was buried in Lincoln Park in 1852, when the plot formed the old City Cemetery. There was no stone to mark his grave, and when the removals were made the remains of Kennison were left undisturbed. Forty-four years after, men who honor his memory are attempting to fix the exact point of his grave so that a suitable stone may be erected giving testimony to a life of unusual experience. Among those who visited the park were Henry S. Boutelle, Josiah L. Lombard, George H. Fergus, John Fergus, Fernando Jones, John N. Armstrong, Henry C. Kelly, W.L. Beckwith, and Joseph H. Ernst. The committee, accompanied by Supt. Alexander, went to the west side of the park, near North avenue, where it was known in a general sense that Kennison had been buried. Mr. Ernst pointed out what he thought to be the true place, but Fernando Jones and others who were present at the funeral, when a salute was fired over Kennison’s grave, would not accept Mr. Ernst’s decision as entirely exact, and it was decided to hunt up the map of the cemetery. The latter is supposed to be preserved somewhere in the archives in the City Hall. If it is found all doubt will be removed, otherwise the point selected by the committee yesterday will be accepted and a tablet erected. David Kennison was probably the last survivor of the famous Boston tea party, which sounded the tocsin of the seven years’ struggle for American independence. Kennison was born in Kingston, in the Province of Maine, in 1736. He was a farmer, and came of long-lived stock, his grandfather living to be 115 years old and his father to be 103. He married four times, leaving four children by his first wife, eighteen by the second, and none by the last. Kennison was a member of a secret patriot society at Lebanon, Me., and when the British Government sent its vessels laden with tea into Boston Harbor Kennison and a party of brother patriots, disguised as Indians, boarded the ships, threw tea overboard, and returned to shore before armed resistance could be summoned. Kennison fought all through the Revolutionary war, bearing a musket at Lexington, Bunker Hill, the siege of Boston, the battle of White Plains, Fort Washington, and Saratoga Springs. He also served in the war of 1812. In 1847 he came to Chicago and entered the service of Judge Henry Fuller. He drew a pension from the government, and for a time conducted a museum, himself the greatest curiosity. His funeral was an incident of real local importance, an immense crowd attending at the grave. |

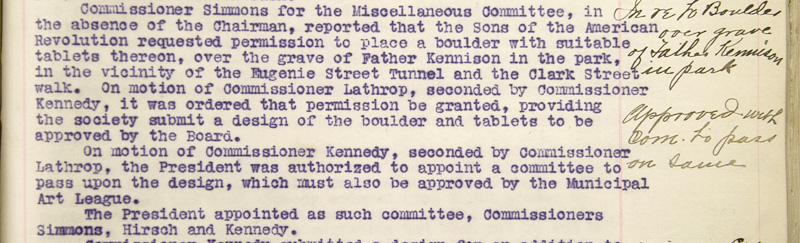

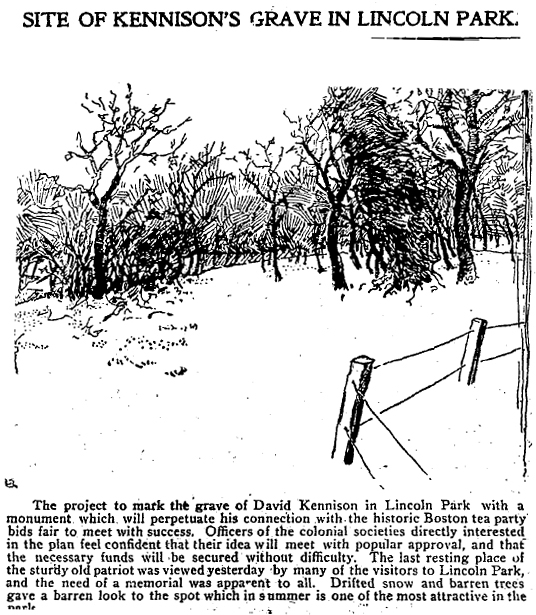

Five years after the last discussion to memorialize the gravesite of David Kennison, it appeared that Fernando Jones, et.al., won the argument over where Kennison was buried.

According to this Chicago Daily Tribune article, below, in 1901 a bronze cross memorialized Kennison near the site where the boulder would be placed nearly three years later.

The article also states that a few years prior, at the suggestion of Fernando Jones, a commemorative medallion of a Minuteman accompanied the bronze cross. Jones had apparently taken it upon himself to promoted David Kennison to an elite rank of Revolutionary soldiers.

The Lincoln Park Commissioners' proceedings minutes from later that year spoke of placing a boulder on Father Kennison's grave at the earlier argued location.

Two months later, on November 21, 1901, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported the boulder would be placed at the site Fernando Jones suggested, where the bronze cross and Minuteman medallion were already in place.

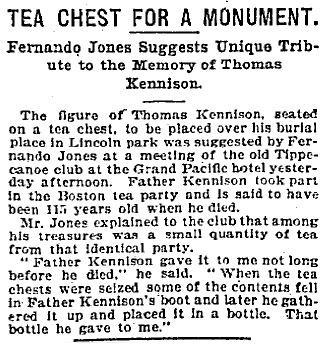

More than a year later, Kennison appears again in the Chicago Daily Tribune, this time as Thomas Kennison. In this February 1, 1903 article, Fernando Jones suggests that a sculpture of David Kennison sitting upon a chest of tea should be erected at the gravesite.

On December 19, 1903, the David Kennison boulder was dedicated near the ground where it rests today, at the foot of Wisconsin Street, near Clark Street.

In 1935, at the suggestion of a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution to remove the boulder to a more "suitable" location, it was moved one hundred feet north, where it remains today.

___________________________________________________________________________

Chicago Daily Tribune, February 24, 1901

|

Lincoln Park Commissioner Proceedings, September 4, 1901 (By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.)

|

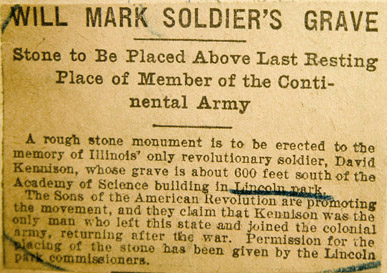

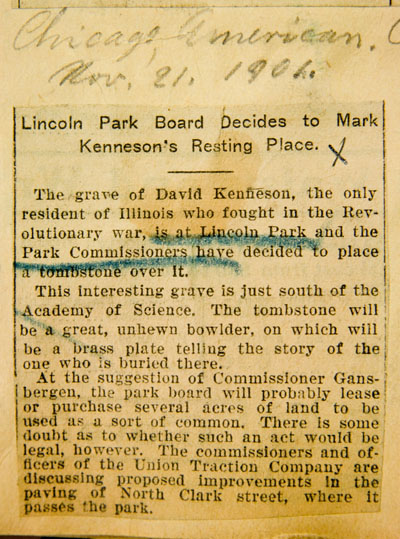

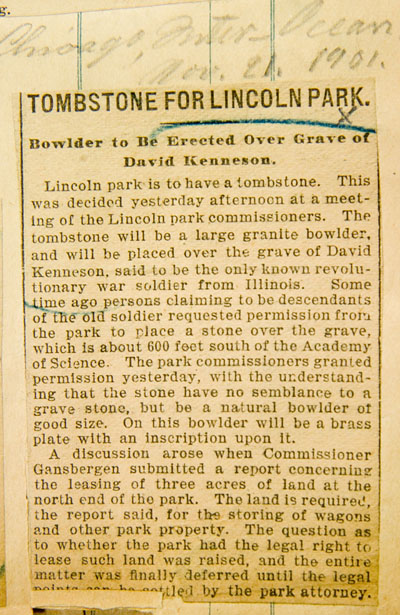

These images of newspaper articles are from a clippings file scrapbook in the Chicago Park District Archive. They are reproduced by permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.

Chicago Record Herald, November 21, 1901

|

These two newspaper articles, below, look to have received similar information for their publication. Kennison is spelled Kenneson, the only time I saw this variation of the name which has also been spelled Kinnison, Kenniston, and Kinniston.

This 1901 discussion of the plan to erect a boulder on the Kennison gravesite led to Fernando Jones' objection to the inappropriateness of such an unseemly memorial to the legacy of David Kennison. (See that story in the Fernando Jones tab, above.)

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, February 25, 1901

Chicago Daily Tribune, February 1, 1903

Chicago Daily Tribune, February 1, 1903

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, November 21, 1901

Chicago Journal, November 21, 1901

Chicago Journal, November 21, 1901

|

|

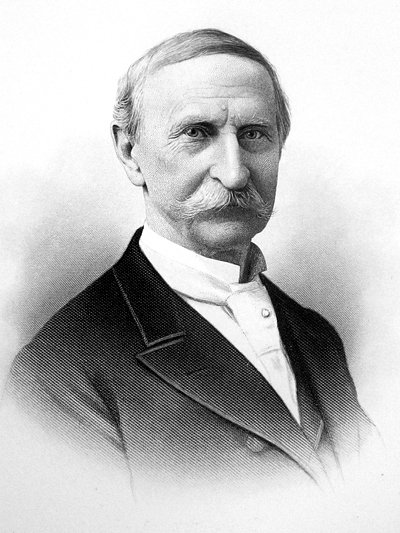

Fernando Jones was another Chicago character, who, like David Kennison, seemed to thrive on the attention of the newspapers of the day. Living to the age of ninety-one, Fernando Jones became an outspoken authority on Early Chicago. Jones was a member of the Chicago Historical Society, where he was known to dress in full Native American Regalia. He claimed to speak fluent Pottowatamie from his boyhood experiences with those Chicago natives. On May 27 1910, at the occasion of Jones' ninetieth birthday, the Chicago Daily Tribune, presented an article titled, "Fernando Jones is Chicago Incarnate." The writer states, "Everybody in Chicago knows about Fernando Jones, even if they never saw him, and a large proportion of the population have had that pleasure, too. From the time he landed here, away back in the dark ages - in 1835 - Mr. Jones has been a celebrated member of the community."

The boulder memorializing David Kennison was placed in Lincoln Park in December 1903. Fernando Jones apparently won the argument concerning the proper location of the gravesite. My research has shown that Fernando Jones was wrong in his recollection. In the 1896 Chicago Daily Tribune article, transcribed to the right here, Jones and others argued with the former City Sexton, Joseph Ernst about the location. Ernst was correct in his memory of where David Kennison was buried. (See The Likely Burial Site section.)

The boulder memorializing David Kennison was placed in Lincoln Park in December 1903. Fernando Jones apparently won the argument concerning the proper location of the gravesite. My research has shown that Fernando Jones was wrong in his recollection. In the 1896 Chicago Daily Tribune article, transcribed to the right here, Jones and others argued with the former City Sexton, Joseph Ernst about the location. Ernst was correct in his memory of where David Kennison was buried. (See The Likely Burial Site section.)

Fernando Jones, born in 1820, lived to be 91, and in his Chicago Daily Tribune obituary on November 9, 1911, he was referred to as “Chicago’s oldest settler.”

In 1912, in the Chicago Historical Society's annual report, there is the acknowledgement of the acquisition of a vial of tea and an affadavit asserting its authenticity.

(See The Artifacts section for more about these objects.) |

When the city officials agreed to pay David Kennison's funeral expenses, they donated the burial site, with the intention of erecting a monument. A monument never installed, and apparently, not even a headstone marked the Kennison grave.

Although Jones said he was at the 1852 David Kennison funeral, which he said gave him the authority to locate the gravesite, he does not appear in the Kennison story until 1894 when he helped place a flag at that supposed site. By this time there was disagreement over the proper location of the Kennison grave. When the boulder was placed at the site Fernando Jones had suggested, nine more years had passed.

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 15, 1894

|

Chicago Post, June 14, 1894

Over a Patriot’s Grave.

Chicago Pioneers Mark last Resting-Place in Lincoln Park of an Historic Character.

Was a member of “Boston Tea-Party”

Died in this city in 1852, Aged 115 – Old settlers’ recollections of him.

************

A little party of Chicago’s oldest settlers went out to Lincoln park this morning to a point near the head of LaSalle avenue and by taking measurements from several old landmarks located the grave of David Kennison, who was the last to die of that historic party of Bostonians that threw the British-taxed tea into the sea.

The old settlers differed a little in their recollections as to distances, so they averaged up the opinions like a jury and planted a bronze marker on what all agreed must be very near the exact spot of the grave. The marker is in the shape of a Grecian cross bearing A.S.R in the three upper arms. In the center is a minute man and the thirteen stars of the original states. In the top is a small United States flag and a card was hung on the cross with the following written lines:

HIC JACET DAVID KENNISON,

the last of the Boston tea party.

Born in the province of Maine, Nov. 17, 1736.

Died in Chicago Feb 24, 1852.

Aged 115 years 3 months and 17 days.

Buried with military honors in the old Chicago cemetery, now Lincoln Park.

May his soul rest in peace.

Standing in a circle about the little cross which rested on the sod, Fernando Jones, Josiah Lombard, Henry Clay Kelly and Charles O. Pratt fell into a reminiscent mood and related incidents of the old revolutionary soldier, who was one of Chicago’s greatest characters fifty years ago. George H. Fergus, who was to have been present, was represented by his son.

Flag day was taken advantage of as an appropriate occasion for locating and marking the old patriot’s last resting-place.

“Yes, sir,” said Fernando Jones, “I’ve got a little bottle of that very tea that was on board the ship the night of the Boston tea party. It is sealed up and I have with it a certificate from Kennison that it is the genuine article. Kennison often related the story of the tea party. He said after he went home and took off the Indian togs which all the fellows wore during the attack on the ship and while they were dumping King George’s tea overboard he found his pockets full of the tea. He put the tea in a canister and took it to his mother, who was fond of good tea, but she would never touch any of King George’s old tea. Kennison thought she would soon get over her prejudice and so she put the tea away in an old cupboard.

“Years rolled on, the war was over, the old Kennison homestead had been sold when David went back one day to the old place. Rummaging around in the garret he found the cupboard and in it the canister of tea just as he had left it. Old Mrs. Kennison had never recovered from her hatred of King George enough to take any of his tea.:

“I am sure that is correct for Kennison was the most honest old fellow you ever saw. He was a genuine Scotchman and whenever he made an assertion it was when he know what he was talking about. About three years before he died, on his 112th birthday, he was given a donation party. It was a big one, I tell you. Everybody came down handsomely, for David was popular. He was superintendent of Monroe’s museum at that time, and, although he wasn’t there as a freak, he was a big card for the show and helped to draw visitors. I was out here at the cemetery the day he was buried, and so were Kelly, Pratt and Fergus.”

“I remember the day well,” said Henry Clay Kelly. “I was powder-boy then in the artillery squad and we stood right over there on that ridge and fired our salute in honor of the old hero.”

“Many a time I’ve heard old ‘Father David’ tell of his life and thrilling experience in the war and before the war among the Indians,” said Charles O. Pratt. “He was once held prisoner by the Indians for eighteen months. One night he was sent by them to a spring to get water and he forgot to come back. The Indians were soon hot on his trail. David crawled in a hollow log. The redskins came up and sat down on the log, but they never again caught the fellow they were sitting on.

“At one time during the revolution he was designated as a messenger to go to George Washington but got caught in a skirmish before he could start. A ball from the enemy struck him directly over the heart and only the big bundle of dispatches in which the bullet lodged saved his life.

“Kennison used to live with relatives at the corner of Madison and Jefferson streets and there was where he spent the last hours of his eventful 115 years. His service was not only in the revolution for he was a soldier in the war of 1812. He outlived four wives. In his later years he lost track of his many children, who were scattered everywhere. He didn’t even know how many were living but I remember one son of whom he spoke was over 80 years of age.”

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, June 10, 1896

FIX THE TOMB OF A HERO.

Grave of David Kennison Nearly Located in Lincoln Park

Committee of the Sons of the American Revolution Seeks the Last Resting Place of a Colonial Patriot – Memorial Statue Will Mark a Historic Spot – Archives of the City Are to Be Searched to Confirm Funeral Memoirs.

The grave of David Kennison, patriot and revolutionary hero, who died in Chicago at the age of 115, was located within a few feet in Lincoln Park yesterday afternoon by a committee composed of members of the Sons of the American Revolution. David Kennison was buried in Lincoln Park in 1852, when the plot formed the old City Cemetery. There was no stone to mark his grave, and when the removals were made the remains of Kennison were left undisturbed. Forty-four years after men who honor his memory are attempting to fix the exact point of his grave so that a suitable stone may be erected giving testimony to a life of unusual experience. Among those who visited the park were Henry S. Boutelle, Josiah L. Lombard, George H. Fergus, John Fergus, Fernando Jones, John N. Armstrong, Henry C. Kelly, W.L. Beckwith, and Joseph H. Ernst. The committee, accompanied by Supt. Alexander, went to the west side of the park, near North avenue, where it was known in a general sense that Kennison had been buried. Mr. Ernst pointed out what he thought to be the true place, but Fernando Jones and others who were present at the funeral, when a salute was fired over Kennison’s grave, would not accept Mr. Ernst’s decision as entirely exact, and it was decided to hunt up the map of the cemetery. The latter is supposed to be preserved somewhere in the archives in the City Hall. If it is found all doubt will be removed, otherwise the point selected by the committee yesterday will be accepted and a tablet erected. David Kennison was probably the last survivor of the famous Boston tea party, which sounded the tocsin of the seven years’ struggle for American independence. Kennison was born in Kingston, in the Province of Maine, in 1736. He was a farmer, and came of long-lived stock, his grandfather living to be 115 years old and his father to be 103. He married four times, leaving four children by his first wife, eighteen by the second, and none by the last. Kennison was a member of a secret patriot society at Lebanon, Me., and when the British Government sent its vessels laden with tea into Boston Harbor Kennison and a party of brother patriots, disguised as Indians, boarded the ships, threw tea overboard, and returned to shore before armed resistance could be summoned. Kennison fought all through the Revolutionary war, bearing a musket at Lexington, Bunker Hill, the siege of Boston, the battle of White Plains, Fort Washington, and Saratoga Springs. He also served in the war of 1812. In 1847 he came to Chicago and entered the service of Judge Henry Fuller. He drew a pension form the government, and for a time conducted a museum, himself the greatest curiosity. His funeral was an incident of real local importance, an immense crowd attending at the grave.

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, February 24, 1901

|

(By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.)

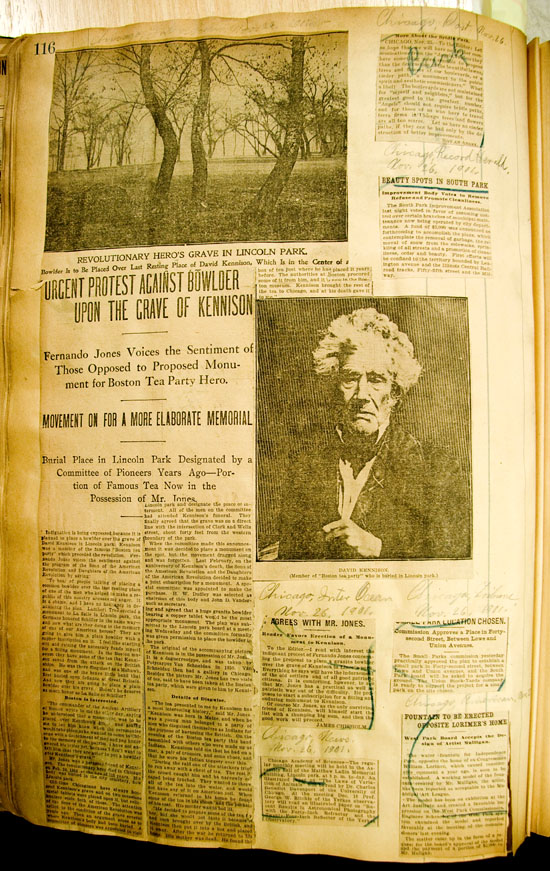

This page from a clippings file scrapbook in the archive of the Chicago Park District, shows the extent of the coverage of the David Kennison story of the decision to place a boulder in Lincoln Park. The main article is from Chicago's Inter Ocean newspaper from November 24, 1901. The text to the article is transcribed on the right. After all this discussion about the boulder, nothing was done on the site until two more years had passed.

|

Chicago Inter Ocean, November 24, 1901

Indignation is being expressed because it is planned to place a bowlder over the grave of David Kennison in Lincoln park. Kennison was a member of the famous “Boston tea party” which preceded the revolution. Fernando Jones voices the sentiment against the program of the Sons of the American Revolution and Daughters of the American Revolution by saying:

“To hear of people talking of placing a common bowlder over the last resting place of one of the men who helped to make a republic of this country arouses my anger. It is a shame, and I have no hesitance in denouncing the plan. Lambert Tree erected a monument to La Salle in Lincoln park, the Germans honored Schiller in the same way – and now what are they doing to the memory of one of our American heroes? They are going to give him a plain bowlder with a copper inscription on it. I feel like starting out and raising the necessary funds myself for a fitting monument. In the Boston museum they have some of the tea that Kennison saved from the attack on the British ships. He was there disguised as a Mohawk, and was one of the brave little band that first hurled open defiance at Great Britain. And now they are going to place a plain bowlder over his grave. Doesn’t he deserve as much honor as La Salle or Schiller?

Boston is Interested.

“The commander of the Ancient Artillery of Boston wrote to me the other day, saying he understood that a monument was to be placed over Kennison’s grave and asking me to let him know when the ceremonies would take place, as he wanted to come to Chicago with a detachment of men and pay honor to the memory of the patriot. I have not answered his letter yet, because I don’t want to tell him that they are going to put a bowlder over Kennison’s grave.”

Mr. Jones was a personal friend of Kennison. The revolutionary here died in Chicago on Feb. 24, 1852 at the age of 115 years. His body was buried in the city cemetery, now Lincoln park.

Old-time Chicagoans have always honored Kennison’s grave and on two occasions metal tablets were placed upon it, but relic-hunters stole both of these. The attention of the Sons of the American Revolution was called to the condition of the grave several years ago. Then an argument arose as to where Kennison’s body had been buried. A committee of pioneers was appointed to visit Lincoln park and designate the place of interment. All of the men on the committee had attended Kennison’s funeral. They finally agreed that the grave was on a direct line with the intersection of Clark and Wells street, about forty feet from the western boundary of the park.

When the committee made this announcement it was decided to place a monument on the spot, but the movement dragged along and was forgotten. Last February, on the anniversary of Kennison’s death, the Sons of the American Revolution and the Daughters of the American Revolution decided to make a joint subscription for a monument. A special committee was appointed to make the purchase. H.W. Dudley was selected as chairman of this body and John D. Vandercook as secretary.

They all agreed that a huge granite bowlder bearing a copper tablet would be the most appropriate monument. The plan was submitted to the Lincoln park board at a meeting Wednesday and the committee formally was given permission to place the bowlder in the park.

The original of the accompanying picture of Kennison is in the possession of Mr. Jones. It is a daguerreotype, and was taken by Polycarpus Van Schneidau in 1850. Van Schneidau then had a gallery in Chicago. Besides the picture Mr. Jones has two vials of tea, said to have been given to him by Kennison.

Details of Disguise.

“The tea presented to me by Kennison has a most interesting history,” said Mr. Jones. “Kennison was born in Main, and when he was a young man belonged to a party of men who disguised themselves as Indians for the purpose of harassing the British. On the evening of the Boston tea party this band assembled with others who were made up as Indians. Kennison told me that he had on a coat, a pair of trousers, and some shoes, and that he wore his Indian toggery over this.

“During the raid one of the attackers tried to run away with a chest of tea. The rest of the crowd caught him and he narrowly escaped being lynched. They wanted to throw all of the tea into the water, and would not have any of it on American soil. When Kennison returned to his home he found some of the tea in his shoes, and the pocket of his coat. His mother was in bed ill.

“He decided to prepare some of the tea for her, but she would not taste it because it had been brought over by the British, and Kennison then put it into a box and placed it away. After the war he returned to his home. His mother was dead. He found the box of tea just where he had placed it years before. The authorities at Boston procured some of it from him, and it is now in the Boston museum. Kennison brought the rest of the tea to Chicago, and at his death gave it to me.”

|

This letter to the editor of the Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper

was written in response to the article transcribed, at the left.

(By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.)

Although never publicly contributing any funds for the erection of a monument to memorialize David Kennison, Fernando Jones had many ideas for ways to commemorate him. In the article below, Jones mentions the tea leaves Kennison supposedly gave him. This is a slightly different version of the same story he told in in the newspaper article on the left, two years earlier.

Although never publicly contributing any funds for the erection of a monument to memorialize David Kennison, Fernando Jones had many ideas for ways to commemorate him. In the article below, Jones mentions the tea leaves Kennison supposedly gave him. This is a slightly different version of the same story he told in in the newspaper article on the left, two years earlier.

Chicago Daily Tribune, February 1, 1903

|

Fernando Jones, as portrayed in the 1912 book, Indian Sketches: Pere Marquette and the Last of the Pottawatomie Chiefs, by Cornelia Steketee Hulst.

|

|