| |

By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.

By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.

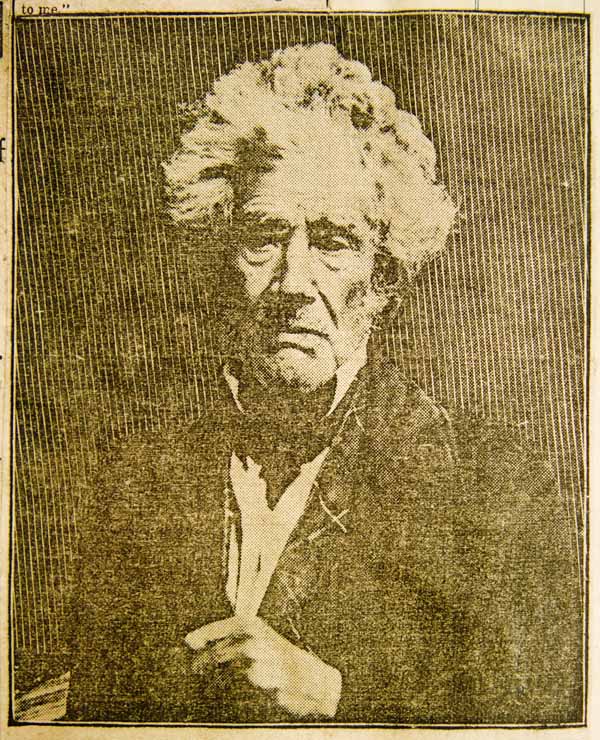

Chicago Inter-Ocean Newspaper, November 24, 1901,

from a photograph dated prior to 1852, current provenance unknown.

This is the only photographic reproduction I have ever seen of David Kennison.

|

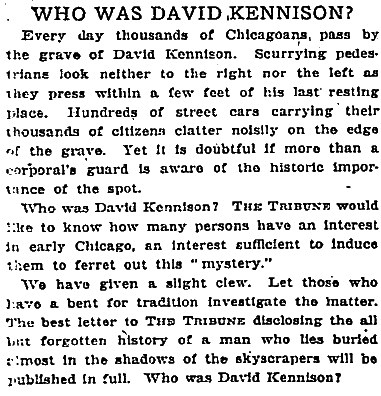

David Kennison's now disputed legacy began with his own supposed statements that were printed in the Chicago Democrat and Chicago Evening Post newspapers. (See the His Stories section.) These stories have often been quoted, and then embellished in later references to Kennison's life. In the April 14, 1919 edition of the Chicago Tribune, the editors put out a call to its readers to answer the question, "Who Was David Kennison?" The newspaper printed those responses, as illustrated below.

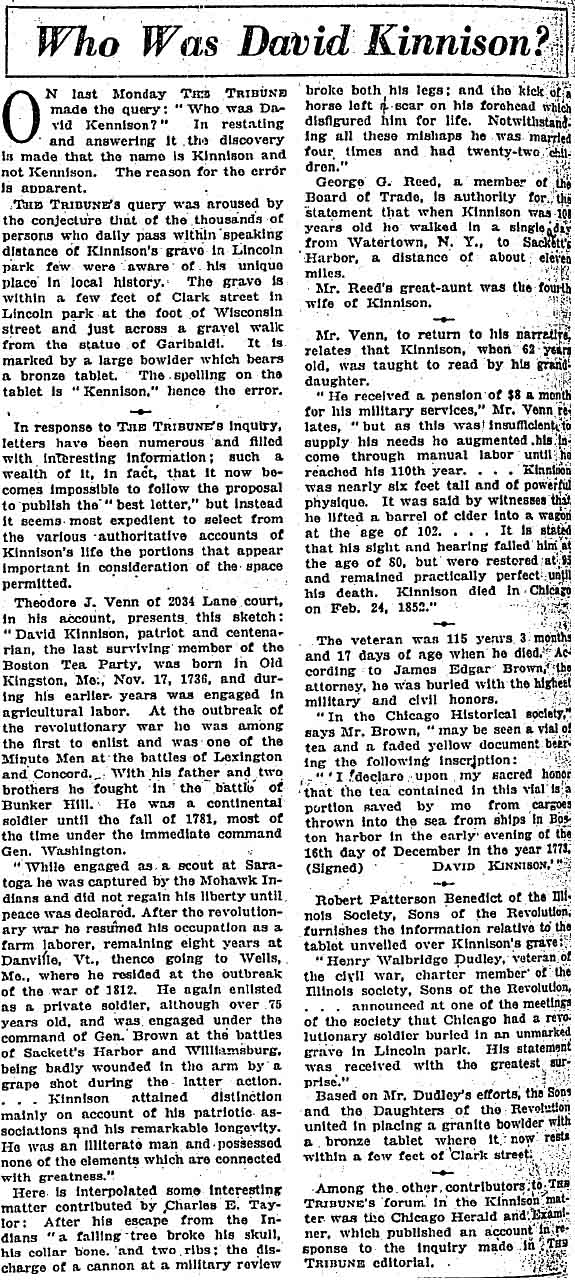

Each of the contributions listed below include some bit of information from the original Kennison statement.

Some items, such as the reference to his hearing and sight being restored at the age of 92, after those faculties were lost at the age of 80, became the first time I encountered such "facts."

A chronological compilation of more recent references and embellishments continue below the 1919 newspaper article. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, April 14, 1919

|

Chicago Daily Tribune, April 18, 1919

Not included in any of the above accounts, are Kennison's exploits related to Fort Dearborn. On July 2, 1915, the Chicago Evening Journal added this story to the legend, placing Kennison in Chicago forty years earlier than ever before mentioned:

… when he was 70 years old he decided he would go out on the prairies of far-away Illinois and take a chance in getting hold of something. This trip was in 1808, and the present site of Chicago, with its watery streets, lit up at night by fireflys and made musical by the chorus of frogs, must have been indeed inviting to one 70 years old and accustomed to the rare culture of old Boston. But the old gentleman remained; he stood by his intention and he became attached to the vicinity. The old Fort Dearborn was “chip new,” and he called on the small garrison and became acquainted with the captain, Nathan Heald, and volunteered as a private. Old as he was, he so impressed the captain that he was quickly accepted. He was on the muster rolls and his name can be seen at the War Department as among those who are early as 1810 and as late as August, 1812, were among Chicago’s defenders.

The terrible and cruel Chicago massacre occurred while he was on the roll, but he fortunately escaped, as he happened to be chosen a messenger to Detroit. He was now 74 years old – think of a man of that age riding horseback thru a wilderness, filled with sneaking Indians, who were bent on wearing hour hair. But David was the real article; he longed and he loved just that daring, adventurous and risky task. When he arrived at his destination, the sad news of the fate of Fort Dearborn was told.

David Kennison's legacy also became associated with the performance profession by way of his job at a Chicago museum, where he mostly presented himself as a live exhibit. Various references mention Kennison performing at either Mooney's or John B. Rice's museum.

A Chicago Daily Tribune article from November 24, 1926, titled, "Stage Folk to Honor Memory of Hero of '76," states, "Members of the theatrical profession in Chicago, both actors and executives, will hold memorial services on Dec. 3 at the grave of David Kennison, who at the time of his death in 1852 was the oldest living person in America associated with the stage." The article speaks of the ceremony as “ushering in the observance of the centennial year of vaudeville in the United States."

Sometimes aspects of the David Kennison legacy are relayed with almost comical frankness. The following excerpt is from Louise DeKoven Bowen's book, Growing Up With A City, originally published in 1926.

"His name was David Kennison; after the massacre his skull was crushed by a falling tree, he had a bad fall later and broke his collar bone and two ribs, the discharge of a faulty cannon broke both his legs, a horse kicked him in the face and smashed in his forehead. Nevertheless he survived all these injuries, was married four times and had twenty-two children; the last two years of his life he entered a museum, as he felt his many adventures made him an object of interest, and his pension was not enough for him to live on. He died in 1852 at the age of 115 years, in full possession of all his faculties."

The 1953 book, Historic Chicago Sites, by George Peter Jensen, hedges a little in regard to Kennison:

"David Kennison is supposed to have been the last survivor of the Boston Tea Party. He survived the massacre of 1812, and died in Chicago in 1852 at the ripe old age of 115 years. What a wealth of history he must have been able to tell – and he left but scant records!"

Two additional excerpts follow:

"It is almost certain that he took part in the desperate fight near Fort Dearborn in 1812, because his name appears on the muster roll of May in that year, although no mention is made of him in any account of the battle or of the survivors. He must, therefore have been one of the survivors who came back from captivity without publicity of any kind, probably having escaped his Indian captors. Too bad he hasn’t left a record of his experiences."

"In 1848 he seems to have been unable to make ends meet in his usual way, because there appeared an advertisement in a local paper as follows: “I have taken the museum in this city (Mooney’s at 73 Lake Street), which I was obliged to do in order to get comfortable living, as my pension is so small it scarcely affords me life. If I live until the 17th of November, 1848, I shall be 112 years old, and I intend making a donation party on that day at the museum. I have fought several battles for my country. All I ask of the generous public is to call at the museum on the 17th of November, which is my birthday, and donate to me what they think I deserve.” Available records do not show success or failure of the party."

In an unsigned Chicago Daily Tribune article from July 4, 1959, the writer makes some new bold assertions:

"He was a Minute Man with Paul Revere, fought at Bunker Hill, and was present at Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown. Later, he joined a regiment that was sent to Fort Dearborn, and was in a detachment that was evacuated before the massacre of August, 1812."

In a short Chicago Tribune article from September 25, 1967, there is a photograph of ten people surrounding the David Kennison boulder, paying tribute to him. The caption identifies an eleven year old girl, pictured, as Kennison's great-great-great-grandniece. The girl and her mother are described as being related through David Kennison's brother. Not only is this the first reference I encountered that mentioned Kennison had a brother, it also identifies him as also being at the Boston Tea Party:

"Mrs. Brown and her daughter are direct descendents of William Kennison, brother of David, who also was at Valley Forge and the Boston Tea Party."

In 1969, in The New Chicago, a Supplement to the New World Vol. LXXVI, No.12, two excerpts from the David Kennison entry reads as follows:

"Injuries aside, during the course of his lifetime he was married four times and had 20, 22, or 24 children, depending upon the source. When he had last heard from his offspring, only seven were still living in the late 1840s. However a book detailing the exploits of Revolutionary War soldiers was published around 1848 and one daughter found out through the book that Kennison was still alive. She rejoined him in his last years and was with him when he died."

"A newspaper interview said that “the last season he gathered one hundred bushels of corn, dug potatoes, made hay, and harvested oats, though this season he is too infirm to work long though he thought he could walk 20 miles in a day by starting early.” He was able to do just that a year before, when he was 110. And he could lift a barrel of rum or cider – sources disagree on the beverage – into a wagon with ease."

Lastly, although there are numerous additional references to David Kennison, this is a recent entertaining summary of his life, from the online version of the Arizona Daily Wildcat's, "Fast facts: Things you always never wanted to know":

"David Kennison, born in 1736, lived to 115 and was the longest surviving participant in the Boston Tea Party. He served in both the American Revolution and the War of 1812. He served in the latter at the age of 76 and had his hand shot off at Sackett's Harbor. Several years later, his skull was fractured when a tree fell on his head and, several years after that, while he was training for a militia drill, a premature explosion from a cannon shattered both his legs. When he recovered from the injury, his legs became covered with sores that never healed, and he was stricken with rheumatism. Some time later, his face was mutilated when he was kicked by a horse. He finally died a quiet death in Illinois in 1851."

|

|

On Chicago's northwest side,

there is a one-block-long street named for David Kennison. |

|