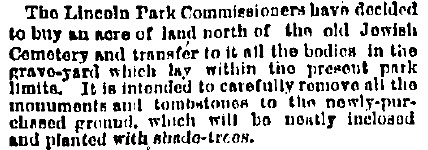

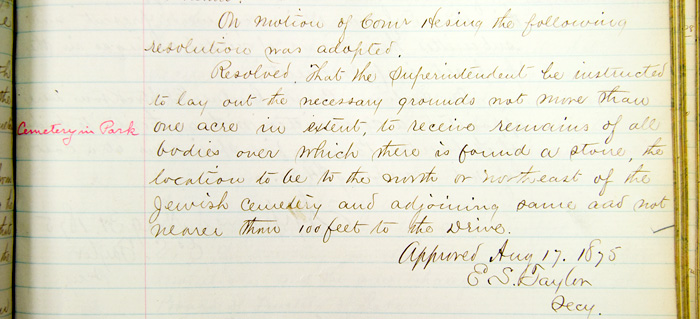

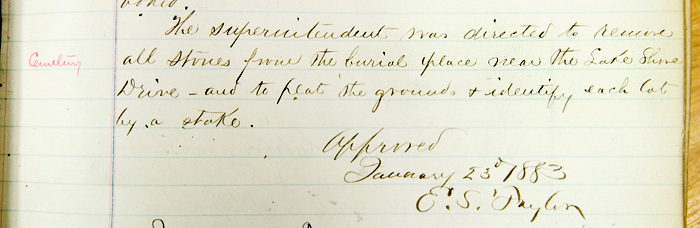

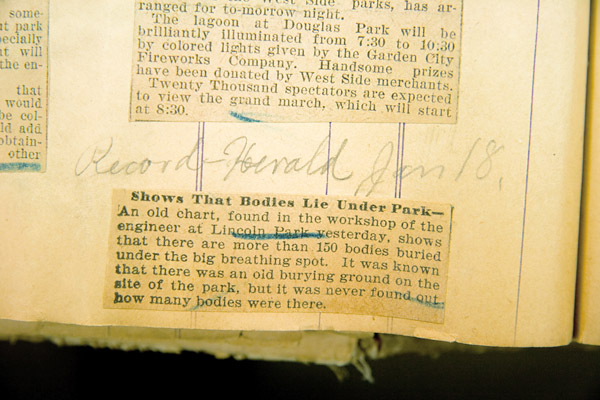

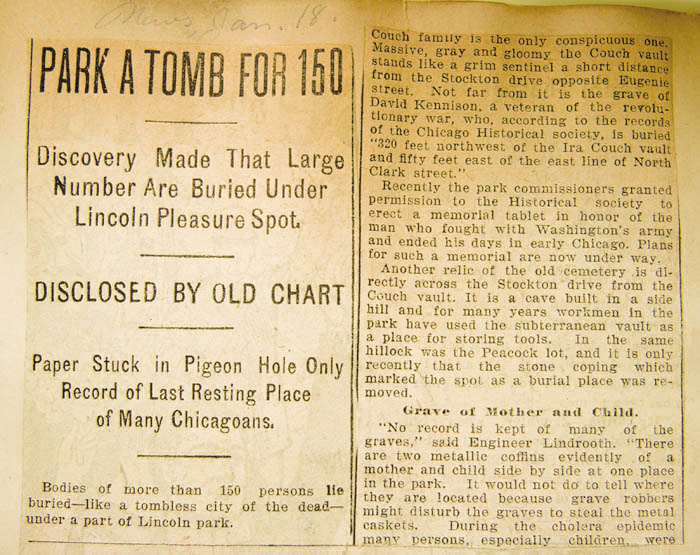

Ten years after the establishment of Lincoln Park, four years after the Chicago Fire, and at a time when the disinterments were presumed to have been completed, there remained cemetery headstones in Lincoln Park, marking graves of individuals who had not been claimed for reinterment elsewhere. Wanting to complete the transition of the cemetery into the park grounds, the Lincoln Park Commissioners moved the scattered marked graves to a separate fenced location within the park. A few years later that Cemetery in the Park was itself incorporated into the park grounds by removing the above-ground evidence. Twenty years later, a park engineer discovered a map detailing the burials from that area. By that time nobody seemed to remember this earlier park feature. ________________________________________________ Chicago Daily Tribune, August 14, 1875  Lincoln Park Commissioners Proceedings, August 17, 1875  By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections. Lincoln Park Commissioners Proceedings, January 23, 1883  By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections. Chicago Record Herald, January 18, 1903  By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections. Chicago News, January 18, 1903  By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections. (transcribed verbatim from the newspaper article, above) Bodies of more than 150 persons lie buried – like a tombless city of the dead – under a part of Lincoln park. Discovery of this fact, hitherto a subject largely of speculation, was made to-day when an old chart was found in the workshop of a park engineer. The bodies have never been removed since the time the site between Wisconsin street and North avenue east of North Clark street was used as a city cemetery. Unmarked by a headstone, not mentioned in official records and unknown to the thousands of persons who frequent the spot, 145 of the bodies lie clustered together at the north end of the baseball field, 130 by 200 feet in dimensions. Scattered throughout the southern part of the park six other bodies, perhaps many more, lie beneath the lawns and tennis courts. In a pigeon hole in the workshop where hundreds of maps, blue prints and drafts are put away year after year the old chart in pencil was found. It had remained undisturbed for years, while the lapse of a quarter of a century obliterated the history of the remnant of the old cemetery which still exists where the romping feet of children tread, where picnic parties hold revelry and where lovers keep their trysts. Of the other bodies still in Lincoln park aside from those in the burying place mentioned the location of four members of the Couch family is the only conspicuous one. Massive, gray and gloomy the Couch vault stands like a grim sentinel a short distance from the Stockton drive opposite Eugenie street. Not far from it is the grave of David Kennison, a veteran of the revolutionary war, who, according to the records of the Chicago Historical society, is buried “320 feet northwest of the Ira Couch vault and fifty feet east of the east line of North Clark street.” Another relic of the old cemetery is directly across the Stockton drive form the Couch vault. It is a cave built in a side hill and for many years workmen in the park have used the subterranean vault as a place for storing tools. In the same hillock was the Peacock lot, and it is only recently that the stone coping which marked the spot as a burial place was removed. “No record is kept of many of the graves,” said Engineer Lindrooth. “There are two metallic coffins evidently of a mother and child side by side at one place in the park. It would not do to tell where they are located because grave robbers might disturb the graves to steal the metal caskets. During the cholera epidemic many persons, especially children, were buried in the cemetery doubtless without a permit and so when it came to reconstructing the site for a park there was difficulty in designating the bodies after the task of removing them was begun in 1870. The old sexton of the cemetery – Schumacher was his name and he died about ten years ago – was indispensable in that work. It was made harder by the fact that in the ‘great fire’ a year later all the records in the city hall were destroyed.” |