The burials in Potter's Field continued for six years after the City passed an ordinance to stop the sale of new lots in the City Cemetery. In addition to the hundreds of cholera victims who were interred there in the summer of 1854, there were thousands of Confederate prisoners of war buried during the years 1862-1865. As mentioned in the opening page of this Potter's Field section, individuals were also laid to rest in graves sometimes marked with headstones and even traditional iron fencing around their plots. Along with trench burials of groups of disease victims and soldiers and a section of maintained burial plots, there were also crude wooden markers and individual burials that were likely not marked at all. It is easy to imagine how bodies could get lost or forgotten during the disinterment stage of the cemetery as the grounds were being converted into Lincoln Park.

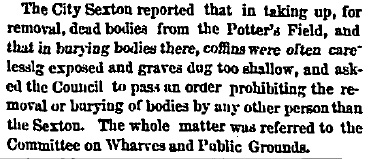

This April 29, 1856 article from the Chicago Tribune illustrates another problem, suggesting that individuals other than the City Sexton were burying bodies, creating an amount of disarray and confusion. The City did not keep detailed records of interments in the potter's field. It was reported elsewhere that undertakers sometimes buried bodies, bypassing the authority of the City Sexton. An editorial published in the same newspaper on April 9, 1866 suggested that undertakers were sometimes burying bodies in newly vacated family lots, effectively bypassing the new ordinance forbidding interments in the potter's field.

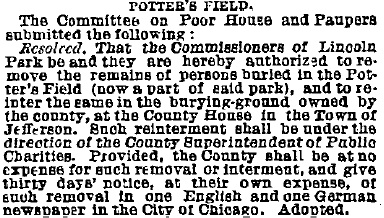

The City began disinterring bodies from Potter's Field in 1872 after the Chicago Fire of 1871 effectively disfigured the lower grounds of the City Cemetery. During this phase of the transition of the grounds into Lincoln Park, all remaining headstones and vaults, with the exception of the Couch Tomb, were removed from the landscape.

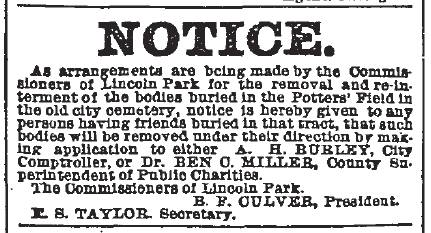

The Chicago Tribune published classified ads for friends of individuals who were buried in the potter's field to arrange for their disinterment.

This ad, below, was published on September 9, 1872.

Chicago Tribune, August 13, 1872

|

Chicago Tribune, September 18, 1872

(Note: Other documents claimed that more than 3000 Confederate soldiers were removed to Oakwoods Cemetery. No other reports ever claimed that these soldiers were removed to Jefferson.)

|

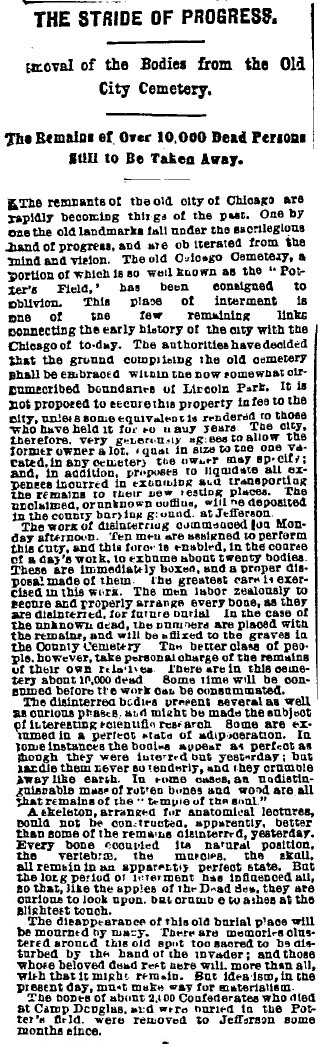

This Chicago Tribune article estimates very conservatively that more than 10,000 individuals are buried in the potter's field.

Stating that the ten men assigned to exhume the bodies are able remove twenty per day, it would seem that the necessary time needed to complete the task was more than five hundred days. On October 13, twenty-five days later, the Tribune reported that the job would be complete within the week.

_____________________________

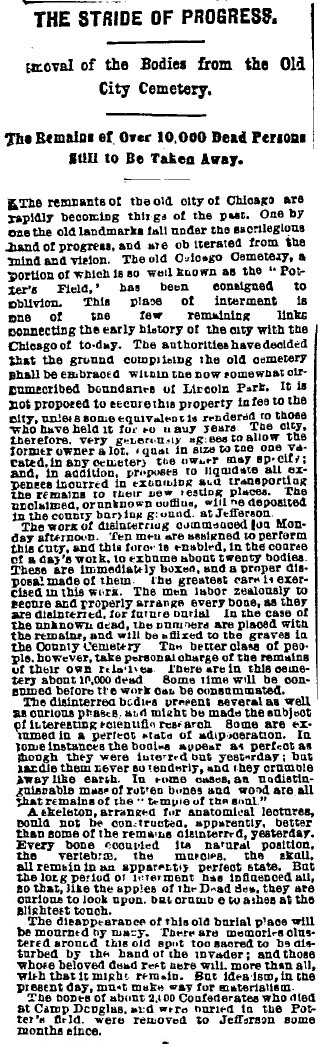

THE STRIDE OF PROGRESS

Removal of the Bodies from the Old City Cemetery.

The Remains of Over 10,000 Dead Persons Still to Be Taken Away.

The remnants of the old city of Chicago are rapidly becoming things of the past. One by one the old landmarks fall under the sacrilegious hand of progress, and are obliterated from the mind and vision. The old Chicago Cemetery, a portion of which is so well known as the “Potter’s Field,” has been consigned to oblivion. This place of interment is one of the few remaining links connecting the early history of the city with the Chicago of to-day. The authorities have decided that the ground comprising the old cemetery shall be embraced within the now somewhat circumscribed boundaries of Lincoln Park. It is not proposed to secure this property in fee to the city, unless some equivalent is rendered to those who have held it for so many years. The city, therefore, very generously agrees to allow the former owner a lot, equal in size to the one vacated, in any cemetery the owner may specify; and, in addition, proposes to liquidate all expenses incurred in exhuming and transporting the remains to their new resting places. The unclaimed, or unknown coffins, will be deposited in the county burying ground at Jefferson.

The work of disinterring commenced on Monday afternoon. Ten men are assigned to perform this duty, and this force is enabled, in the course of a day’s work, to exhume about twenty bodies. These are immediately boxed, and a proper disposal made of them. The greatest care is exercised in this work. The men labor zealously to secure and properly arrange every bone, as they are disinterred, for future burial. In the case of the unknown dead, the numbers are placed with the remains, and will be affixed to the graves in the County Cemetery. The better class of people, however, take personal charge of the remains of their own relatives. There are in this cemetery about 10,000 dead. Some time will be consumed before the work can be consummated.

The disinterred bodies present several as well as curious phases, and might be made the subject of interesting scientific research. Some are exhumed in a perfect state of adipoceration. In some instances the bodies appear as perfect as though they were interred but yesterday; but handle them never so tenderly, and they crumble away like earth. In some cases, an indistinguishable mass of rotten bones and wood are all that remains of the “temple of the soul.”

A skeleton, arranged for anatomical lectures, could not be constructed, apparently, better than some of the remains disinterred, yesterday. Every bone occupied in its natural position, the vertebrae, the muscles, the skull, all remain in an apparently perfect state. But that long period of interment has influenced all, so that, like the apples of the Dead Sea, they are curious to look upon, but crumble to ashes at the slightest touch.

The disappearance of this old burial place will be mourned by many. There are memories clustered around this old spot too sacred to be disturbed by the hand of the invader; and those whose beloved dead rest here will, more than all, wish that it might remain. But idealism, in the present day, must make way for materialism.

The bones of about 2,000 Confederates who died at Camp Douglas, and were buried in the Potter’s field were removed to Jefferson some months since. |