| |

The book, The Catholic Church in Chicago, 1673-1871: An Historical Sketch, by Gilbert J. Garraghan is a good source of the early history of this Church in Chicago. Published in 1921, it can be viewed in its entirety on the Google Book SearchTM Web Site. Click here to see the book.

Another resource, also viewable on Google Book SearchTM, is A History of the Catholic Church Within the Limits of the United States, published in 1892. View that book here.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

The French-born John Mary Irenaeus St. Cyr was the first priest assigned to the town of Chicago. Responding to a petition signed by thirty-six early Chicago residents, the Bishop of the diocese in St. Louis appointed St. Cyr in the spring of 1833.

The petition:

We, the Catholics of Chicago, Cook Co., Ill., lay before you the necessity there exists to have a pastor in this new and flourishing city. There are here several families of French descent, born and brought up in the Roman Catholic faith and others quite willing to aid us in supporting a pastor, who ought to be sent here before other sects obtain the upper hand, which very likely they will try to do. We have heard several persons say were there a priest here they would join our religion in preference to any other. We count almost one hundred Catholics in this town. We will not cease to pray until you have taken our important request into consideration.

April 16, 1833

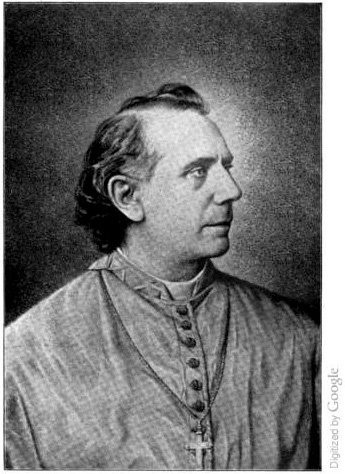

(quote above, from A.T. Andreas' History of Chicago, Vol. 1, p. 289; portraits, right, and below, from A History of the Catholic Church within the Limits of the United States.)

In 1836, the German-born Bernard Schaeffer joined St. Cyr as the second Catholic priest. St. Cyr left the following year, leaving Schaeffer to minister to Chicago's Catholics until he died in the summer of that same year. |

Bishop William Quarter: 1844-1848

|

Bishop James Oliver Van de Velde: 1848-1853

|

At his death in the summer of 1837, Bernard Schaeffer was replaced by his assistant, the Irish born Bernard O'Meara.

In 1840, the French-born Maurice de St. Palais replaced O'Meara.

The Irish-born William Quarter was the first Bishop of Chicago, arriving at that post in May 1844. Quarter is responsible for the establishment of several early Catholic institutions, including the first university, the first parish school, and the first high school for the Catholic faithful. In 1846 he brought, from Pittsburgh, six nuns from the Religious Order of the Sisters of Mercy. They founded the first girls' school and later a hospital. On the east edge of the Catholic Cemetery plat, appear the words "Sisters Property." The Chicago Title and Trust records indicate those grounds belonged to the University of St. Mary of the Lakes.

Bishop William Quarter died in 1848, at the age of 42, after four years in Chicago. Within those four years, thirty Catholic churches were built and he ordained twenty-nine priests.

Quarter was succeeded by the Belgian-born Rt. Rev. James Oliver Van de Velde. Bishop Van de Velde held that position from 1848-1853, spanning the early years of the Catholic Cemetery.

The Irish-born Rt. Rev. Anthony O'Regan replaced Bishop Van de Velde, when the latter applied to leave Chicago on account of ill health. During Bishop O'Regan's four-year tenure he bought the grounds that would become Calvary Cemetery, near the southern border of the town of Evanston, ten miles north of Chicago. |

Speaking of O'Regan on page 128 in The Catholic Church in Chicago, Garraghan writes: for the shabby cottage in which Bishop Quarter and Van de Velde had lodged, he substituted an episcopal residence of a style commensurate with the dignity of a great Catholic diocese. Built of marble and brick on property at the northwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Madison Street, it was finished in 1856 and was reputed in its day one of the most handsome residences in the city.

Bishop O'Regan's tenure is tainted with accusations by French-speaking Catholics that he treated their parishes unfairly. As part of a January 27, 1857, editorial in the Chicago Daily Tribune, the writer exclaims,

There are at least 15,000 French Catholics in Chicago and Kankakee, or, at least, Catholics who speak the French language. These people are more liberal in their sentiments toward Protestants, and less submissive to priestly dictation than any other class of Catholics. For possessing this spirit of religious independence, they are persecuted by the Irish Bishop with a malevolence that is shocking and insufferable. These French Catholics have made their appeal to the great American Public, for justice and sympathy.

See the Cardinal Accusations section, on the left, for the story by the Rev. Charles Chiniquy, a French Canadian assigned to a parish in Kankakee, Illinois. Chiniquy's accusations escalate to include O'Regan selling the sands on the Lake Michigan shore at the east edge of the Catholic Cemetery. Chiniquy claimed the sand contained skeletal remains from the burial ground.

In 1857, Bishop O'Regan went to Rome to apply for release of his Chicago appointment. Upon his resignation, O'Regan was made a Bishop in London, England, where he died nine years later at the age of fifty-seven.

|

Bishop Anthony O'Regan: 1854-1858

|

Bishop James Duggan: 1859-1869

|

The Irish-born James Duggan replaced Bishop O'Regan and inherited the disgruntled parishoners who felt like pawns in O'Regan's quest to acquire more city land for the Catholic Church. During the Chicago real estate collapse of 1857, O'Regan had been accused of selling French Catholics' church property and real estate, while at the same time building himself a residential palace.

Bishop James Duggan's tenure covered the Civil War years and a period of continued real estate growth with the building of sixteen new churches ten years. In 1866 Duggan had a wood frame eight-bed hospital erected on the corner of Dearborn and Schiller Streets . It is not clear on which corner the building stood, but the northeast quadrant had been the Catholic cemetery grounds since 1845. By 1871 there were nine Catholic hospitals and orphan asylums in Chicago.

After a rift with the administration of a local Catholic university, Duggan's legacy becomes confusing. Various written sources delicately phrase his ambiguous demise: "The latter days of Bishop Duggan's administration were clouded by the unfortunate controversies that arose between him and certain influential members of his clergy. Only after a long-drawn out and painful period of misunderstanding and dissension was the variableness of purpose ... recognized as a premonitory state of complete mental collapse." 1 "It was at this period that the final giving away of a vigorous and brilliant intellect led to various complications in the Diocese ... The incipient insanity of Bishop Duggan could not escape the eyes of those who were familiar with him."2"... he had already begun to show signs of the mental abberation that ultimately caused the unfortunate man to spend the last thirty years of his life in an insane asylum."3

|

The last few years of Duggan's appointment were important in the history of the movement of the cemetery grounds. Because the Catholic cemetery was privately held, there are no records representing its history in the City's files. By 1872, the new Bishop Foley was speaking of laying out streets and selling the burial grounds.

There was no official Catholic Bishop in Chicago during the year following Bishop Duggan's removal to an insane asylum. In 1870, the Rt. Rev. Thomas Foley became the first American-born Chicago Bishop. By this time, the City Cemetery grounds were transitioning to become Lincoln Park. An original plan of Lincoln Park included the construction of a drive made of lakefill to connect the park with what would become Michigan Avenue. The City needed to acquire the easement rights to lakefront lands occupied by the Catholic cemetery. See more about this transaction, and the laying out of the grounds into residential streets in the Selling The Land section.

After the Chicago Fire in 1871, Bishop Foley had the difficult task of overseeing the rebuilding of destroyed churches and other Catholic institutions, including the burial grounds on the lakeshore. The Chicago Fire accounts of people fleeing the fire by jumping into open graves in the Catholic and City cemeteries attest to the ongoing exhumations to the newer cemeteries outside the city limits. After the Fire, the ravaged landscapes of both cemeteries expedited their process of transformation into grounds for other uses.

Bishop Foley died in Chicago in 1879. |

Bishop Thomas

Foley: 1870-1879

|

Archbishop Patrick Augustine Feehan: 1880-1901

|

This contemporary aerial view from the Google Earth TM Web Site shows the 1885 Catholic mansion and estate grounds, surrounded by highrises in Chicago's Gold Coast neighborhood. Lincoln Park is across North Boulevard at the top of the photograph.

Click here to see the grounds in a larger context.

|

In 1880, when the city was raised to an archdiocese from a diocese, the Irish-born Rt. Rev. Patrick Feehan became the Chicago's first archbishop.

Archbishop Feehan's legacy includes selling the residentially-platted Catholic burial grounds and building his own estate within those grounds. In January 1882, construction began on his mansion that remains today in the Gold Coast neighborhood, overlooking Lincoln Park. The Catholic Church-owned estate occupies the largest parcel of land in the area previously covered by the old graveyard.

In a May 22, 2002 New York Times article, Chicago Cardinal Proposes Selling His Mansion, Jodi Wilgoren said, "Now Cardinal Francis E. George wants to sell the place. He says it is too much house for a humble servant of God. And, the cardinal said, the estimated $15 million price could keep the deficit-laden archdiocese from closing more schools, or help pay sexual abuse settlements."

The Cardinal continues to occupy the estate in 2008.

___________________________________________________

|

1 The Catholic Church in Chicago, 1673-1871: An Historical Sketch, Gilbert J. Garraghan, Loyola Univ. Press, 1921, p.218

2 The Life and Wrtitings of the Right Reverend John McMullan, D.D., James McGovern, Hoffman Brothers, 1888., p.176.

3 Essays on Seminary Education, John Tracy Ellis, Fides Publishers, 1967., p.162. |

|