The Couch Tomb is never mentioned in the Lincoln Park Commissioner's Proceedings, which duly recorded the amounts paid to lot owners for the quitclaim deeds to their cemetery properties. This suggests to me that the Couch family did not seek compensation for their property and the removal of the vault. It also implies that the commissioners did not attempt to compensate the Couch family in any way. If there was any discussion related to the Couch lot, there is no record of it.

The Lincoln Park Commissioner minutes:

The President pointed out the advisability of purchasing the Peacock cemetery lot with a view to recasting the grounds in that locality. On motion the President was given power to negotiate and make a deal for the same if found practicable.

In 1895, the Lincoln Park Commissioners paid the Peacock family $1000 for their several lots of cemetery property, upon which stood their family tomb. I found no Supreme Court reference detailing a Peacock case, as mentioned below. By 1903, only the vault's stone coping remained.

On October 7, 1900, the Chicago Tribune wrote this:

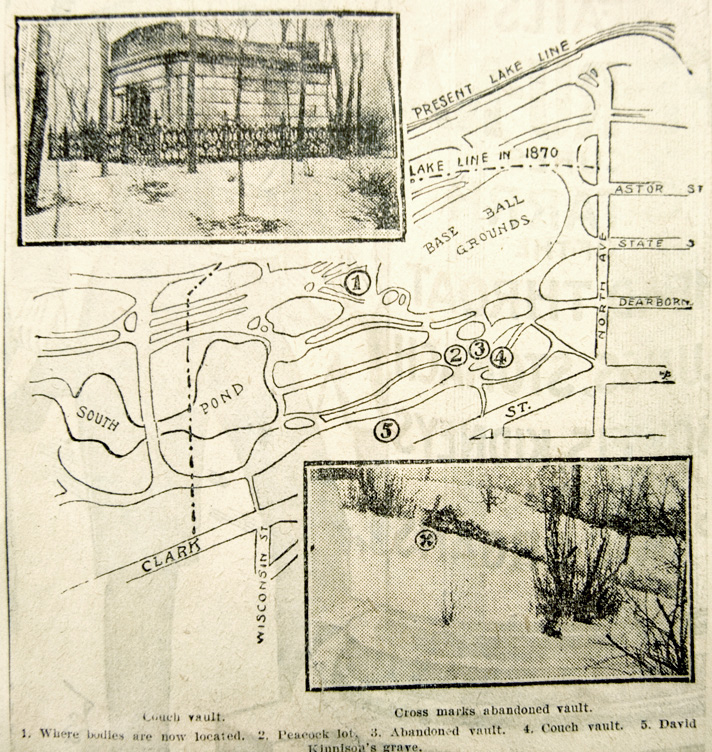

This illustration, at the right, accompanied a January 12, 1903, Chicago News newspaper article, and showed, among other things, that there was yet another vault left behind in the park. This one, located between the Couch and Peacock properties, appears to have been a sunken model. It was assumed that the vault was empty, as the article stated that park workers stored their tools within it.

The illustration also shows the correct general location (5) of the David Kennison grave, two blocks south of the boulder that was meant to mark that spot.

The context of this Chicago News article was to report that a park worker had found a chart "stuck in a pigeonhole" in an engineer's workshop. This chart contained the locations of one hundred fifty graves that were removed to an area just north of the former Jewish cemetery. This so-called "cemetery in the park" was formed in 1875 to deposit the remains from the graves that were still marked after the lot condemnations and disinterments were accounted for at that point. (Families continued to remove their loved ones' apparently unmarked remains until 1887.)

Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1875

In the twenty-seven years since the grounds were reportedly marked and enclosed, all evidence of the distinctly unpark-like area was erased.

The engineeer who found the chart would not divulge the exact locations of the graves because he said that there was a mother and child buried side-by-side, each in iron coffins. He was afraid grave robbers might steal them for the metal. |

By permission and courtesy of the Chicago Park District Special Collections.

|